Slovakia /sloʊˈvɑːkiə/ or /sləˈvækiə/ (officially the Slovak Republic; Slovak: Slovensko (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈslovɛnsko]), long form Slovenská republika (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈslovɛnskaː ˈrɛpublɪka] )) is a sovereign state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about 49,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi). Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south. The largest city is the capital, Bratislava, and the second largest is Košice. Slovakia is a member state of the European Union, Eurozone, Schengen Area, NATO, the United Nations, the OECD and the WTO, among others. The official language is Slovak, a member of the Slavic language family.

Slovakia /sloʊˈvɑːkiə/ or /sləˈvækiə/ (officially the Slovak Republic; Slovak: Slovensko (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈslovɛnsko]), long form Slovenská republika (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈslovɛnskaː ˈrɛpublɪka] )) is a sovereign state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about 49,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi). Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south. The largest city is the capital, Bratislava, and the second largest is Košice. Slovakia is a member state of the European Union, Eurozone, Schengen Area, NATO, the United Nations, the OECD and the WTO, among others. The official language is Slovak, a member of the Slavic language family.

The Slavs—ancestors of the Slovaks—arrived in the territory of present-day Slovakia in the 5th and 6th centuriesduring the migration period. In the 7th century, Slavs inhabiting this territory played a significant role in the creation of Samo’s Empire, historically the first Slavic state which had its center in Western Slovakia. During the 9th century, Slavic ancestors of the Slovaks established another political entity, the Principality of Nitra, which later together with the Principality of Moravia, formed Great Moravia. After the 10th century the territory of today’s Slovakia was gradually integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary, which itself became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire or Habsburg Empire. After WWI and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the nation of Slovaks and Czechs established their mutual state – Czechoslovakia. A separate Slovak state existed during World War II and was a client state of Nazi Germany (from 1939 to 1944). In 1945 Czechoslovakia was reestablished. The present-day Slovakia became an independent state on 1 January 1993 after the peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia.

The Slavs—ancestors of the Slovaks—arrived in the territory of present-day Slovakia in the 5th and 6th centuriesduring the migration period. In the 7th century, Slavs inhabiting this territory played a significant role in the creation of Samo’s Empire, historically the first Slavic state which had its center in Western Slovakia. During the 9th century, Slavic ancestors of the Slovaks established another political entity, the Principality of Nitra, which later together with the Principality of Moravia, formed Great Moravia. After the 10th century the territory of today’s Slovakia was gradually integrated into the Kingdom of Hungary, which itself became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire or Habsburg Empire. After WWI and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the nation of Slovaks and Czechs established their mutual state – Czechoslovakia. A separate Slovak state existed during World War II and was a client state of Nazi Germany (from 1939 to 1944). In 1945 Czechoslovakia was reestablished. The present-day Slovakia became an independent state on 1 January 1993 after the peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia.

Slovakia is a high-income advanced economy with one of the fastest growth rates in the European Union and the OECD. The country joined the European Union in 2004 and the Eurozone on 1 January 2009.

History

Radiocarbon dating puts the oldest surviving archaeological artifacts from Slovakia – found near Nové Mesto nad Váhom – at 270,000 BC, in the Early Paleolithic era. These ancient tools, made by the Clactonian technique, bear witness to the ancient habitation of Slovakia.

Other stone tools from the Middle Paleolithic era (200,000 – 80,000 BC) come from the Prévôt (Prepoštská) cave near Bojnice and from other nearby sites. The most important discovery from that era is a Neanderthal cranium (c. 200,000 BC), discovered near Gánovce, a village in northern Slovakia.

Archaeologists have found prehistoric human skeletons in the region, as well as numerous objects and vestiges of the Gravettian culture, principally in the river valleys of Nitra, Hron, Ipeľ, Váh and as far as the city of Žilina, and near the foot of the Vihorlat, Inovec, and Tribeč mountains, as well as in the Myjava Mountains. The most well-known finds include the oldest female statue made of mammoth-bone (22,800 BC), the famous Venus of Moravany. The statue was found in the 1940s in Moravany nad Váhom near Piešťany. Numerous necklaces made of shells from Cypraca thermophile gastropods of the Tertiary period have come from the sites of Zákovská, Podkovice, Hubina, and Radošinare. These findings provide the most ancient evidence of commercial exchanges carried out between the Mediterranean and Central Europe.

Bronze age

hwest Slovakia. Copper became a stable source of prosperity for the local population.

After the disappearance of the Čakany and Velatice cultures, the Lusatian people expanded building of strong and complex fortifications, with the large permanent buildings and administrative centers. Excavations of Lusatian hill forts document the substantial development of trade and agriculture at that period. The richness and the diversity of tombs increased considerably. The inhabitants of the area manufactured arms, shields, jewelry, dishes, and statues.

Iron age

Hallstatt Period

The arrival of tribes from Thrace disrupted the people of the Kalenderberg culture, who lived in the hamlets located on the plain (Sereď) and in the hill forts like Molpír, near Smolenice, in the Little Carpathians. During Hallstatt times, monumental burial mounds were erected in western Slovakia, with princely equipment consisting of richly decorated vessels, ornaments and decorations. The burial rites consisted entirely of cremation. The common people were buried in flat urnfield cemeteries. A special role was given to weaving and the production of textiles. The local power of the “Princes” of the Hallstatt period disappeared in Slovakia during the last century before the middle of first millennium BCE, after strife between the Scytho-Thracian people and locals, resulting in abandonment of the old hill-forts. Relatively depopulated areas soon caught interest of emerging Celtic tribes, who advanced from the south towards the north, following the Slovak rivers, peacefully integrating into the remnants of the local population.

La Tène Period

From around 500 BC, the territory of modern-day Slovakia was settled by Celts, who built powerful oppida on the sites of modern-day Bratislava and Devin. Biatecs, silver coins with inscriptions in the Latin alphabet, represent the first known use of writing in Slovakia. At the northern regions, remnants of the local population of Lusatian origin, together with Celtic and later Dacian influence, gave rise to the unique Puchov culture, with advanced crafts and iron-working, many hill-forts and fortified settlements of central type with coinage of the “Velkobysterecky” type (no inscriptions, with a horse on one side and a head on the other). This culture is often connected with the Celtic tribe mentioned in Roman sources as Cotini.

Roman Period

From 2 AD, the expanding Roman Empire established and maintained a series of outposts around and just north of the Danube, the largest of which were known as Carnuntum (whose remains are on the main road halfway between Vienna and Bratislava) and Brigetio (present-day Szöny at the Slovak-Hungarian border). Such Roman border settlements were built on the present area of Rusovce, currently a suburb of Bratislava. The military fort was surrounded by a civilian vicus and several farms of the villa rustica type. The name of this settlement was Gerulata. The military fort had an auxiliary cavalry unit, approximately 300 horses strong, modeled after the Cananefates. The remains of Roman buildings have also survived in Devin castle (present-day downtown Bratislava), the suburbs of Dubravka and Stupava, and Bratislava Castle Hill.

Near the northernmost line of the Roman hinterlands, the Limes Romanus, there existed the winter camp of Laugaricio (modern-day Trenčín) where the Auxiliary of Legion II fought and prevailed in a decisive battle over the Germanic Quadi tribe in 179 AD during the Marcomannic Wars. The Kingdom of Vannius, a kingdom founded by the Germanic Suebian tribes of Quadi and Marcomanni, as well as several small Germanic and Celtic tribes, including the Osi and Cotini, existed in Western and Central Slovakia from 8–6 BC to 179 AD.

Great invasions from the 4th to 7th centuries

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, the Huns began to leave the Central Asian steppes. They crossed the Danube in 377 AD and occupied Pannonia, which they used for 75 years as their base for launching looting-raids into Western Europe. However, Attila’s death in 453 brought about the disappearance of the Hun tribe. In 568, a Turko-Mongol tribal confederacy, the Avars, conducted its own invasion into the Middle Danube region. The Avars occupied the lowlands of the Pannonian Plain, and established an empire dominating the Carpathian Basin.

In 623, the Slavic population living in the western parts of Pannonia seceded from their empire after a revolution led by Samo, a Frankish merchant. After 626, the Avar power started a gradual decline but its reign lasted to 804.

Slavic states

The Slavic tribes settled in the territory of present-day Slovakia in the 5th century. Western Slovakia was the centre of Samo’s empire in the 7th century. A Slavic state known as the Principality of Nitra arose in the 8th century and its ruler Pribina had the first known Christian church of Slovakia consecrated by 828. Together with neighboring Moravia, the principality formed the core of the Great Moravian Empire from 833. The high point of this Slavonic empire came with the arrival of Saints Cyril and Methodius in 863, during the reign of Prince Rastislav, and the territorial expansion under King Svatopluk I.

Great Moravia (830–before 907)

Great Moravia arose around 830 when Mojmír I unified the Slavic tribes settled north of the Danube and extended the Moravian supremacy over them. When Mojmír I endeavoured to secede from the supremacy of the king of East Francia in 846, King Louis the German deposed him and assisted Moimír’s nephew Rastislav (846–870) in acquiring the throne. The new monarch pursued an independent policy: after stopping a Frankish attack in 855, he also sought to weaken influence of Frankish priests preaching in his realm. Rastislav asked the Byzantine Emperor Michael III to send teachers who would interpret Christianity in the Slavic vernacular.

Upon Rastislav’s request, two brothers, Byzantine officials and missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius came in 863. Cyril developed the first Slavic alphabet and translated the Gospel into the Old Church Slavonic language. Rastislav was also preoccupied with the security and administration of his state. Numerous fortified castles built throughout the country are dated to his reign and some of them (e.g., Dowina, sometimes identified with Devín Castle) are also mentioned in connection with Rastislav by Frankish chronicles.

During Rastislav’s reign, the Principality of Nitra was given to his nephew Svatopluk as an appanage. The rebellious prince allied himself with the Franks and overthrew his uncle in 870. Similarly to his predecessor, Svatopluk I (871–894) assumed the title of the king (rex). During his reign, the Great Moravian Empire reached its greatest territorial extent, when not only present-day Moravia and Slovakia but also present-day northern and central Hungary, Lower Austria, Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia, southern Poland and northern Serbia belonged to the empire, but the exact borders of his domains are still disputed by modern authors. Svatopluk also withstood attacks of the semi-nomadic Magyar tribes and the Bulgarian Empire, although sometimes it was he who hired the Magyars when waging war against East Francia.

In 880, Pope John VIII set up an independent ecclesiastical province in Great Moravia with Archbishop Methodius as its head. He also named the German cleric Wiching the Bishop of Nitra.

After the death of Prince Svatopluk in 894, his sons Mojmír II (894–906?) and Svatopluk II succeeded him as the Prince of Great Moravia and the Prince of Nitra respectively. However, they started to quarrel for domination of the whole empire. Weakened by an internal conflict as well as by constant warfare with Eastern Francia, Great Moravia lost most of its peripheral territories.

In the meantime, the semi-nomadic Magyar tribes, possibly having suffered defeat from the similarly nomadic Pechenegs, left their territories east of the Carpathian Mountains, invaded the Carpathian Basin and started to occupy the territory gradually around 896. Their armies’ advance may have been promoted by continuous wars among the countries of the region whose rulers still hired them occasionally to intervene in their struggles.

We do not know what happened with both Mojmír II and Svatopluk II because they are not mentioned in written sources after 906. In three battles (4–5 July and 9 August 907) near Bratislava, the Magyars routed Bavarian armies. Some historians put this year as the date of the breakup of the Great Moravian Empire, due to the Hungarian conquest; other historians take the date a little bit earlier (to 902).

Great Moravia left behind a lasting legacy in Central and Eastern Europe. The Glagolitic script and its successor Cyrillic were disseminated to other Slavic countries, charting a new path in their sociocultural development. The administrative system of Great Moravia may have influenced the development of the administration of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Kingdom of Hungary (1000–1918)

hen the Austro-Hungarian empire collapsed, the territory of modern Slovakia was an integral part of the Hungarian state. The ethnic composition became more diverse with the arrival of the Carpathian Germans in the 13th century, and the Jews in the 14th century.

A significant decline in the population resulted from the invasion of the Mongols in 1241 and the subsequent famine. However, in medieval times the area of the present-day Slovakia was characterized rather by burgeoning towns, construction of numerous stone castles, and the cultivation of the arts. In 1465, King Matthias Corvinus founded the Hungarian Kingdom’s third university, in Pressburg (Bratislava), but it was closed in 1490 after his death.

Before the Ottoman Empire’s expansion into Hungary and the occupation of Buda in 1541, the capital of the Kingdom of Hungary (under the name of Royal Hungary) moved to Pressburg (in Slovak: Prešporok at that time, currently Bratislava). Pressburg became the capital city of the Royal Hungary in 1536. But the Ottoman wars and frequent insurrections against the Habsburg Monarchy also inflicted a great deal of devastation, especially in the rural areas. As the Turks withdrew from Hungary in the late 17th century, the importance of the territory comprising modern Slovakia decreased, although Pressburg retained its status as the capital of Hungary until 1848, when it was transferred to Buda.

During the revolution of 1848–49, the Slovaks supported the Austrian Emperor, hoping for independence from the Hungarian part of the Dual Monarchy, but they failed to achieve their aim. Thereafter relations between the nationalities deteriorated (see Magyarization), culminating in the secession of Slovakia from Hungary after World War I.

Czechoslovakia (1918–1939)

In 1918, Slovakia and the regions of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Carpathian Ruthenia formed a common state, Czechoslovakia, with the borders confirmed by the Treaty of Saint Germain and Treaty of Trianon. In 1919, during the chaos following the breakup of Austria-Hungary, Czechoslovakia was formed with numerous Germans and Hungarians within the newly set borders. A Slovak patriot Milan Rastislav Štefánik (1880–1919), who helped organize Czechoslovak regiments against Austria-Hungary during the First World War, died in a plane crash. In the peace following the World War, Czechoslovakia emerged as a sovereign European state. It provided what were at the time rather extensive rights to its minorities and remained the only democracy in this part of Europe in the interwar period.

During the Interwar period, democratic Czechoslovakia was allied with France, and also with Romania and Yugoslavia (Little Entente); however, the Locarno Treaties of 1925 left East European security open. Both Czechs and Slovaks enjoyed a period of relative prosperity. There was progress in not only the development of the country’s economy, but also culture and educational opportunities. The minority Germans came to accept their role in the new country and relations with Austria were good. Yet the Great Depression caused a sharp economic downturn, followed by political disruption and insecurity in Europe.

Thereafter Czechoslovakia came under continuous pressure from the revisionist governments of Germany and Hungary. Eventually this led to the Munich Agreement of September 1938, which allowed Nazi Germany to partially dismember the country by occupying what was called the Sudetenland, a region with a German-speaking majority and bordering Germany and Austria. The remainder of “rump” Czechoslovakia was renamed Czecho-Slovakia and included a greater degree of Slovak political autonomy. Southern and eastern Slovakia, however, was reclaimed by Hungary at the First Vienna Award of November 1938.

World War II

After the Munich Agreement and its Vienna Award, Nazi Germany threatened to annex part of Slovakia and allow the remaining regions to be partitioned by Hungary or Poland unless independence was declared. Thus, Slovakia seceded from Czecho-Slovakia in March 1939 and allied itself, as demanded by Germany, with Hitler’s coalition.[36] The government of the First Slovak Republic, led by Jozef Tiso and Vojtech Tuka, was strongly influenced by Germany and gradually became a puppet regime in many respects.

Most Jews were deported from the country and taken to German death camps. Thousands of Jews, however, remained to labor in Slovak work camps in Sereď, Vyhne, and Nováky. Tiso, through the granting of presidential exceptions, has been credited with saving as many as 40,000 Jews during the war, although other estimates place the figure closer to 4,000 or even 1,000. Nevertheless, under Tiso’s government, the vast majority of Slovakia’s Jewish population (between 75,000-105,000 individuals) were murdered. Tiso became the only European leader to pay Nazi authorities to deport his country’s Jews.

After it became clear that the Soviet Red Army was going to push the Nazis out of eastern and central Europe, an anti-Nazi resistance movement launched a fierce armed insurrection, known as the Slovak National Uprising, near the end of summer 1944. A bloody German occupation and a guerilla war followed. The territory of Slovakia was liberated by Soviet and Romanian forces by the end of April 1945.

Communist party rule (1948–1989)

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reconstituted and Jozef Tiso was hanged in 1947 for collaboration with the Nazis. More than 80,000 Hungarians and 32,000 Germans were forced to leave Slovakia, in a series of population transfers initiated by the Allies at the Potsdam Conference. This expulsion is still a source of tension between Slovakia and Hungary. Out of about 130,000 Carpathian Germans in Slovakia in 1938, by 1947 only some 20,000 remained.

Czechoslovakia came under the influence of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact after a coup in 1948. The country was occupied by the Warsaw Pact forces (with the exception of Romania) in 1968, ending a period of liberalization under the leadership of Alexander Dubček. In 1969 Czechoslovakia became a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic.

Establishment of the Slovak Republic (1992-)

The end of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia in 1989, during the peaceful Velvet Revolution, was followed once again by the country’s dissolution, this time into two successor states. In July 1992 Slovakia, led by Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar, declared itself a sovereign state, meaning that its laws took precedence over those of the federal government. Throughout the autumn of 1992, Mečiar and Czech Prime Minister Václav Klaus negotiated the details for disbanding the federation. In November the federal parliament voted to dissolve the country officially on 31 December 1992.

The Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic went their separate ways after 1 January 1993, an event sometimes called the Velvet Divorce. Slovakia has remained a close partner with the Czech Republic. Both countries cooperate with Hungary and Poland in the Visegrád Group. Slovakia became a member of NATO on 29 March 2004 and of the European Union on 1 May 2004. On 1 January 2009, Slovakia adopted the Euro as its national currency.

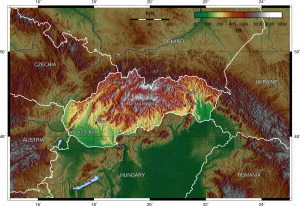

Geography

Slovakia lies between latitudes 47° and 50° N, and longitudes 16° and 23° E.

Slovakia lies between latitudes 47° and 50° N, and longitudes 16° and 23° E.

The Slovak landscape is noted primarily for its mountainous nature, with the Carpathian Mountains extending across most of the northern half of the country. Amongst these mountain ranges are the high peaks of the Fatra-Tatra Area (including Tatra mountains, Greater Fatra and Lesser Fatra), Slovak Ore Mountains, Slovak Central Mountains or Beskids. The largest lowland is the fertile Danubian Lowland in the southwest, followed by the Eastern Slovak Lowland in the southeast.

Tatra mountains

Tatras, with 29 peaks higher than 2,500 metres (8,202 feet) AMSL, are the highest mountain range in the Carpathian Mountains. Tatras occupy an area of 750 square kilometres (290 sq mi), of which the greater part 600 square kilometres (232 sq mi) lies in Slovakia. They are divided into several parts.

To the north, close to the Polish border, are the High Tatras which are a popular hiking and skiing destination and home to many scenic lakes and valleys as well as the highest point in Slovakia, the Gerlachovský štít at 2,655 metres (8,711 ft) and the country’s highly symbolic mountain Kriváň. To the west are the Western Tatras with their highest peak of Rysy at 2,503 metres (8,212 ft) and to the east are the Belianske Tatras, smallest by area.

Separated from the Tatras proper by the valley of the Váh river are the Low Tatras, with their highest peak of Ďumbier at 2,043 metres (6,703 ft).

The Tatra mountain range is represented as one of the three hills on the coat of arms of Slovakia.

National Parks

There are 9 national parks in Slovakia:

| Name | Established | Area |

|---|---|---|

| Tatra National Park | 1949 | 738 square kilometres (73,800 ha) |

| Low Tatras National Park | 1978 | 728 square kilometres (72,800 ha) |

| Veľká Fatra National Park | 2002 | 404 square kilometres (40,400 ha) |

| Slovak Karst National Park | 2002 | 346 square kilometres (34,600 ha) |

| Poloniny National Park | 1997 | 298 square kilometres (29,800 ha) |

| Malá Fatra National Park | 1988 | 226 square kilometres (22,600 ha) |

| Muránska planina National Park | 1998 | 203 square kilometres (20,300 ha) |

| Slovak Paradise National Park | 1988 | 197 square kilometres (19,700 ha) |

| Pieniny National Park | 1967 | 38 square kilometres (3,800 ha) |

Caves

Slovakia has hundreds of caves and caverns under its mountains, out of which 15 are open to the public. Most of the caves have stalagmites rising from the ground and stalactites hanging from above. There are currently five Slovak caves under UNESCO’s World Heritage Site status. They are Dobšinská Ice Cave, Domica, Gombasek Cave, Jasovská Cave and Ochtinská Aragonite Cave. Other caves open to public include Belianska Cave, Demänovská Cave of Liberty, Demänovská Ice Cave or Bystrianska Cave

Rivers

Most of the rivers stem in Slovak mountains. Some are only passing through and the others make a natural border with surrounding countries (more than 620 kilometres (385 mi)). For example Dunajec (17 kilometres (11 mi)) to the north, Danube (172 kilometres (107 mi)) to the south or Morava (119 kilometres (74 mi)) to the West. The total length of the rivers on Slovak territory is 49,774 kilometres (30,928 mi).

The longest river in Slovakia is Váh (403 kilometres (250 mi)), the shortest is Čierna voda. Other important and large rivers are Myjava, Nitra (197 kilometres (122 mi)), Orava, Hron (298 kilometres (185 mi)), Hornád (193 kilometres (120 mi)), Slaná (110 kilometres (68 mi)), Ipeľ (232 kilometres (144 mi), making the border with Hungary), Bodrog, Laborec, Latorica and Ondava.

The biggest volume of discharge in Slovak rivers is during spring, when the snow is melting from the mountains. The only exception is Danube, whose discharge is the biggest during summer when the snow is melting in the Alps. Danube is the largest river that flows through Slovakia.

Lakes

There are around 175 naturally formed tarns in High Tatras. With an area of 20 ha and its depth of 53 metres (174 ft), Veľké Hincovo pleso is the largest and the deepest tarn in Slovakia. Other tarns in the High Tatras include Štrbské pleso, Popradské pleso, Skalnaté pleso, Zbojnícke pleso, Velické pleso, Žabie pleso, Krivánske zelené pleso or Roháčske plesá. Other than in the High Tatras there are Vrbické pleso in Low Tatras, Morské oko and Vinné jazero in Vihorlat Mountains or Jezerské jazero in Spišská Magura.

The largest dams on the river Váh are Liptovská Mara and Sĺňava. Other well known dams are Oravská priehrada in the north, Zemplínska Šírava and Domaša in the east, Senecké jazerá, Zlaté piesky or Zelená voda in the west.

Climate

The Slovak climate lies between the temperate and continental climate zones with relatively warm summers and cold, cloudy and humid winters. Temperature extremes are in interval between −41 to 40.3 °C (−41.8 to 104.5 °F) although temperatures below −30 °C (−22 °F) are rare. The weather differs from the mountainous North to the plain South.

The warmest region is Bratislava and Southern Slovakia where the temperatures may rise up to 30 °C (86 °F) in summer, occasionally to 37 °C (99 °F). During night, the temperatures rise up to 20 °C (68 °F). The daily temperatures in winter average in the range of −5 °C (23 °F) up to 10 °C (50 °F). During night it may be freezing, but usually not below −10 °C (14 °F).

Summer in Northern Slovakia is usually mild with temperatures around 25 °C (77 °F) (less in the mountains). Winters are colder in the mountains, where the snow usually lasts until March and April and the night temperatures go down to −20 °C (−4 °F) and colder.

Biodiversity

Slovakia signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 19 May 1993, and became a party to the convention on 25 August 1994.[52] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which was received by the convention on 2 November 1998.

The biodiversity of Slovakia comprises animals (such as annellids, arthropods, molluscs, nematodes and vertebrates), fungi (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota and Zygomycota), micro-organisms (including Mycetozoa), and plants.

Fungi

Over 4000 species of fungi have been recorded from Slovakia. Of these, nearly 1500 are lichen-forming species Some of these fungi are undoubtedly endemic, but not enough is known to say how many. Of the lichen-forming species, about 40% have been classified as threatened in some way. About 7% are apparently extinct, 9% endangered, 17% vulnerable, and 7% rare. The conservation status of non-lichen-forming fungi in Slovakia is not well documented, but there is a red list for its larger fungi.

Tourism

Slovakia features natural landscapes, mountains, caves, medieval castles and towns, folk architecture, spas and ski resorts. More than 1.6 million people visited Slovakia in 2006, and the most attractive destinations are the capital of Bratislava and the High Tatras. Most visitors come from the Czech Republic (about 26%), Poland (15%) and Germany (11%).

Typical souvenirs from Slovakia are dolls dressed in folk costumes, ceramic objects, crystal glass, carved wooden figures, črpáks (wooden pitchers), fujaras (a folk instrument on the UNESCO list) and valaškas (a decorated folk hatchet) and above all products made from corn husks and wire, notably human figures.

Souvenirs can be bought in the shops run by the state organization ÚĽUV (Ústredie ľudovej umeleckej výroby – Center of Folk Art Production). Dielo shop chain sells works of Slovak artists and craftsmen. These shops are mostly found in towns and cities.

Prices of imported products are generally the same as in the neighboring countries, whereas prices of local products and services, especially food, are usually lower.