26. China/Guangxi: Spending an evening and a night in Guilin (Lijiang River Scenic Zone (UNESCO World Heritage Site))

Guilin, is a prefecture-level city in the northeast of China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. It is situated on the west bank of the Li River and borders Hunan to the north. Its name means “forest of sweet osmanthus”, owing to the large number of fragrant sweet osmanthus trees located in the region. The city has long been renowned for its scenery of karst topography.

Guilin is one of China’s most popular tourist destinations, and the epithet “By water, by mountains, most lovely, Guilin” (山水甲天下) is often associated with the city. The State Council of China has designated Guilin a National Famous Historical and Cultural City, doing so in the first edition of the list.

Guilin is one of China’s most popular tourist destinations, and the epithet “By water, by mountains, most lovely, Guilin” (山水甲天下) is often associated with the city. The State Council of China has designated Guilin a National Famous Historical and Cultural City, doing so in the first edition of the list.

The Wandelgek went to his hotel and checked into his new hotel room for the night.

The Wandelgek went to his hotel and checked into his new hotel room for the night.

Guilin Bravo Hotel

This large hotel with long corridors looked quite fancy, like e.g. the small lamps …

Bed room

… and the design and color (white) of the furniture in the rooms. It all had an old French vibe to it

It felt all luxureous but in a historic way …

After a short rest and a shower, he met with his guide Tao in the hotel lobby and then started on an evening city walk. He first walked to the beautiful …

Rongshanhu Scenic Area

Rongshanhu Scenic Area is the quiet heart of downtown Guilin, where the city loosens its tie and slips into something softer: two linked lakes, Rong (Banyan) Lake and Shan (Fir) Lake, clasped by stone bridges, old trees, and the slow shimmer of water.

At night, when the streets thin out, the surface of the lakes becomes a dark mirror for golden pagodas and lantern-lit paths, turning the whole place into a living ink painting.

At night, when the streets thin out, the surface of the lakes becomes a dark mirror for golden pagodas and lantern-lit paths, turning the whole place into a living ink painting.

Rongshanhu Scenic Area is an urban lake park built around Rong Lake in the west and Shan Lake in the east, connected by narrow necks of water and graceful bridges. It sits in the very center of Guilin, so you step straight from shops and traffic into a ring of water, trees, and distant karst silhouettes floating behind the city skyline.

Rongshanhu Scenic Area is an urban lake park built around Rong Lake in the west and Shan Lake in the east, connected by narrow necks of water and graceful bridges. It sits in the very center of Guilin, so you step straight from shops and traffic into a ring of water, trees, and distant karst silhouettes floating behind the city skyline.

For The Wandelgek, the first enchantment is simply walking: lakeside promenades under banyan and fir trees, stone balustrades, and small pavilions where couples linger to watch the ripples. Many travelers time their visit for evening, when the Sun and Moon Pagodas rise from Shan Lake like twin lanterns on the water, their reflections trembling with every breeze. Boat tours trace glowing paths across the dark water, slipping beneath illuminated bridges and past willow branches that nearly touch the lake, while photographers line the shore to capture the double image of pagodas and city lights. Because entrance to the lakeside area itself is free and easily reached on foot from nearby streets, it often becomes the gentle epilogue to a day of caves, rice terraces, and Li River scenery.

For The Wandelgek, the first enchantment is simply walking: lakeside promenades under banyan and fir trees, stone balustrades, and small pavilions where couples linger to watch the ripples. Many travelers time their visit for evening, when the Sun and Moon Pagodas rise from Shan Lake like twin lanterns on the water, their reflections trembling with every breeze. Boat tours trace glowing paths across the dark water, slipping beneath illuminated bridges and past willow branches that nearly touch the lake, while photographers line the shore to capture the double image of pagodas and city lights. Because entrance to the lakeside area itself is free and easily reached on foot from nearby streets, it often becomes the gentle epilogue to a day of caves, rice terraces, and Li River scenery.

Rongshanhu is not only decoration; it is part of the old water system that has shaped Guilin’s life for centuries, a reminder that this city grew up hugging rivers and lakes as natural defenses, trade routes, and sources of daily sustenance. The banyan and fir trees that give the lakes their names hint at older Guilin, when shade, roots, and water framed the rhythms of markets, festivals, and evening gatherings long before neon arrived.

Rongshanhu is not only decoration; it is part of the old water system that has shaped Guilin’s life for centuries, a reminder that this city grew up hugging rivers and lakes as natural defenses, trade routes, and sources of daily sustenance. The banyan and fir trees that give the lakes their names hint at older Guilin, when shade, roots, and water framed the rhythms of markets, festivals, and evening gatherings long before neon arrived.

Live music

In the velvet hush of Rongshanhu’s evenings, where Rong Lake and Shan Lake cradle the city’s lights like whispered secrets, locals gather as gentle minstrels, their voices and strings weaving romance into the air.

Beneath ancient banyans and firs, they form intimate circles—elders with erhus humming like lovers’ sighs, young couples strumming guitars, and voices rising in community song that drifts across the water like mist-kissed petals. In the movie above, the lady sitting to the utmost left plays an Erhu. The erhu (Chinese: 二胡) is a Chinese two-stringed bowed musical instrument, more specifically a spike fiddle, that is sometimes known in the Western world as the Chinese violin or a Chinese two-stringed fiddle. It is used as a solo instrument as well as in small ensembles and large orchestras. It is the most popular of the huqin family of traditional bowed string instruments used by various ethnic groups of China. As a very versatile instrument, the erhu is used in both traditional and contemporary music arrangements, such as pop, rock and jazz. Beneath you can see three erhu players to the right

Traditional Chinese music (中国传统音乐, Zhōngguó chuántǒng yīnyuè) is an ancient river of sound, flowing through thousands of years of history and spirit. Unlike Western music, which builds its beauty from harmony and structured form, Chinese music drifts toward the intangible—tone, color, and resonance. Each note carries the breath of mountains and the murmur of rivers, echoing the rhythm of wind, the stillness of mist, and the pulse of human emotion interwoven with nature’s voice.

Traditional Chinese music (中国传统音乐, Zhōngguó chuántǒng yīnyuè) is an ancient river of sound, flowing through thousands of years of history and spirit. Unlike Western music, which builds its beauty from harmony and structured form, Chinese music drifts toward the intangible—tone, color, and resonance. Each note carries the breath of mountains and the murmur of rivers, echoing the rhythm of wind, the stillness of mist, and the pulse of human emotion interwoven with nature’s voice.

It is more than melody—it is meditation. Each phrase unfolds as a dialogue between earth and sky, shaped by the wisdom of Confucian balance, the quiet flow of Daoist harmony, and the cosmic patterns of Chinese philosophy. In that sense, its essence mirrors the same contemplative spirit found in the art of Chinese landscape painting and in the serene minimalism of the photography I reflected upon in earlier blogposts about this journey.

These aren’t grand stages but spontaneous heartsongs: a fiddler drawing bow across strings by the glass bridge, his melody chasing fireflies over the lake; a chorus of neighbors harmonizing folk tunes from Guangxi’s hills, their laughter blending with the fountain’s soft spray. As lanterns glow on the Sun and Moon Pagodas, the music swells—raw, unpolished passion that invites passersby to sway, link arms, or steal a glance across the rippling surface.

Sun and Moon pagodas

Today the Sun and Moon Pagodas form a modern cultural icon, fusing Buddhist symbolism with Guilin’s love of theatrical night scenery, and they are often used as a visual shorthand for the city itself.

Today the Sun and Moon Pagodas form a modern cultural icon, fusing Buddhist symbolism with Guilin’s love of theatrical night scenery, and they are often used as a visual shorthand for the city itself.

In a way, Rongshanhu Scenic Area is Guilin’s living memory: an everyday park that still carries the poetic ideals of Chinese landscape art—water, stone, trees, and light arranged so that a simple stroll can feel like stepping into a poem.

In a way, Rongshanhu Scenic Area is Guilin’s living memory: an everyday park that still carries the poetic ideals of Chinese landscape art—water, stone, trees, and light arranged so that a simple stroll can feel like stepping into a poem.

This living serenade is Guilin’s soul laid bare: locals sharing heritage through melodies born of rice fields and rivers, turning a simple stroll into a rendezvous with melody and memory. Picture yourself there, hand in hand, as a lone voice croons of eternal love under the stars—Rongshanhu’s truest romance, free as the breeze, eternal as the karsts.

This living serenade is Guilin’s soul laid bare: locals sharing heritage through melodies born of rice fields and rivers, turning a simple stroll into a rendezvous with melody and memory. Picture yourself there, hand in hand, as a lone voice croons of eternal love under the stars—Rongshanhu’s truest romance, free as the breeze, eternal as the karsts.

South gate

Guilin’s Ancient South Gate stands sentinel on the northern shore of Rong Lake within Rongshanhu Scenic Area, a weathered Tang Dynasty remnant (rebuilt) whispering tales of ancient travelers crossing its threshold under starlit skies, framed by the lake’s gentle lap and a millennium-old banyan tree’s embrace.

Guilin’s Ancient South Gate stands sentinel on the northern shore of Rong Lake within Rongshanhu Scenic Area, a weathered Tang Dynasty remnant (rebuilt) whispering tales of ancient travelers crossing its threshold under starlit skies, framed by the lake’s gentle lap and a millennium-old banyan tree’s embrace.

A seller of lanters contributes to the colorfullness of this environment. Paper lanterns are likely derived from earlier lanterns that used other types of translucent material like silk, horn, or animal skin. The material covering was used to prevent the flame in the lantern from being extinguished by wind, while still retaining its use as a light source. Papermaking technology originated from China from at least AD 105 during the Eastern Han dynasty, but it is unknown exactly when paper became used for lanterns. Poems about paper lanterns start to appear in Chinese history at around the 6th century. Paper lanterns were common by the Tang dynasty (AD 690–705), and it was during this period that the first annual lantern festival was established. From China, it was spread to neighboring cultures in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

A seller of lanters contributes to the colorfullness of this environment. Paper lanterns are likely derived from earlier lanterns that used other types of translucent material like silk, horn, or animal skin. The material covering was used to prevent the flame in the lantern from being extinguished by wind, while still retaining its use as a light source. Papermaking technology originated from China from at least AD 105 during the Eastern Han dynasty, but it is unknown exactly when paper became used for lanterns. Poems about paper lanterns start to appear in Chinese history at around the 6th century. Paper lanterns were common by the Tang dynasty (AD 690–705), and it was during this period that the first annual lantern festival was established. From China, it was spread to neighboring cultures in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

It always reminds me of the Zhang Yimou movie Raise the Red Lantern, which starred actress Gong Li in one of her very best roles …

Zhongshan Road

Zhongshan Middle Road pulses as Guilin’s vibrant commercial spine, threading right through Rongshanhu’s heart, where neon signs flicker like fireflies and evening crowds weave between boutiques, silk emporiums, and jade stalls under the karst silhouette. It’s the perfect nocturnal promenade, alive with the scent of street eats and the chatter of locals bartering treasures. Sugar cane drink sellers line the curbs with hand-cranked presses, squeezing fresh golden nectar into cups—sweet, earthy elixir chilled with lime, a cooling kiss for hot nights.

Shops brim with intricate drawings and calligraphy scrolls, artists at work sketching misty mountains and lovers’ poems on rice paper, inviting you to claim a piece of Guilin’s soul. Restaurants cluster nearby, from steamy noodle houses like Chong Shan MiFen slinging rice vermicelli in fragrant broths, to Chunji Roasted Goose with crispy skins and savory bites, and Kali Mirch wafting Indian spices—all mere steps from the lakeside glow.

Chunji was closed though so we went to another restaurant. First The Wandelgek tried this for him new lager beer …

… which tasted really good in this warm weather …

Next was some delicious looking food with rice and meat and bamboo …

The price looked good too …

After dinner Tao and me strolled through this brightly lit shopping/mainstreet of Guilin …

There were lanterns hanging above the street, reflected by the mirroring pavement …

… Above was a restaurant which seemed to have a Reed Flute Cave theme on the first floor …

… Above was a restaurant which seemed to have a Reed Flute Cave theme on the first floor …

Typical for south east Asia, which includes countries like Vietnam, Indonesia and this part of China, are the many street food bars and stalls on the street. They sell all sorts of south east Asian fast food and drinks…

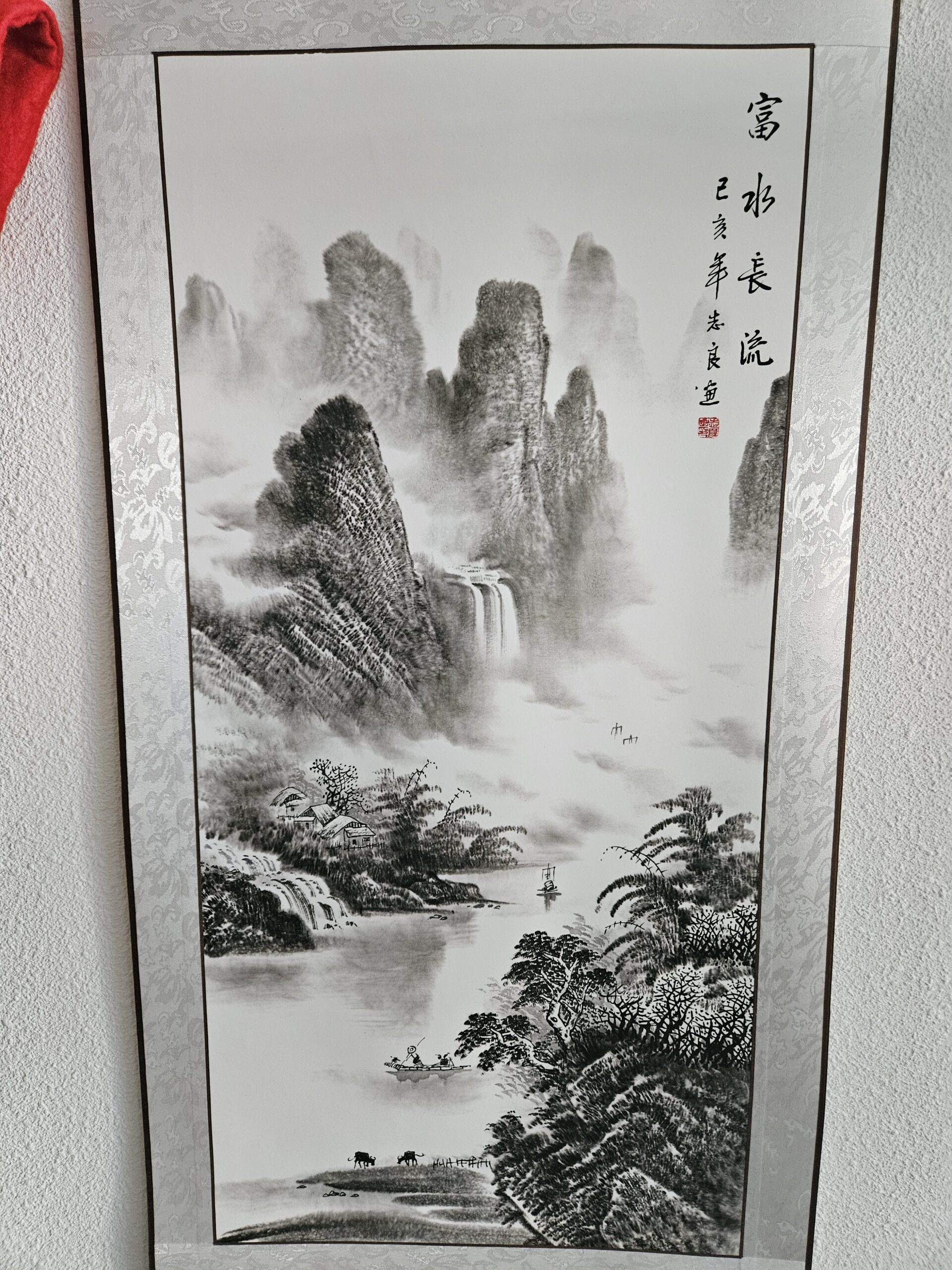

The Wandelgek visited a shop which sold Chinese minimalist ink paintings, where he bought a beautiful painting to decorate his home …

It is a depiction of the area The Wandelgek was visiting right now. The karst hill country of the Lijiang (Li) river …

These paintings are always signed by the artist who created them, using a red ink stamp. It is similar to a signature or better to the often very pictionary ways that modern graffity or street art is signed …

Next The Wandelgek walked back to the lake and slowly in the direction of his hotel …

Colorful glass bridge

The Wandelgek was strolling in a leisurely pace along the lakes edge …

The Wandelgek was strolling in a leisurely pace along the lakes edge …

The colorful glass bridge at Rongshanhu arcs over Rong Lake like a lover’s promise etched in crystal, its transparent surface shimmering with rainbow hues under the night lights, turning each step into a dance on liquid stars reflected below.

The colorful glass bridge at Rongshanhu arcs over Rong Lake like a lover’s promise etched in crystal, its transparent surface shimmering with rainbow hues under the night lights, turning each step into a dance on liquid stars reflected below.

In the hush of evening, as lanterns bloom along the shore, it glows with soft blues, pinks, and golds, inviting you to hold hands and peer through to the velvet water, where your shadows mingle eternally with the ripples.

In the hush of evening, as lanterns bloom along the shore, it glows with soft blues, pinks, and golds, inviting you to hold hands and peer through to the velvet water, where your shadows mingle eternally with the ripples.

Known as the crystal glass bridge, it spans the wide waters of Rong Lake in this open pedestrian park, designed as a modern marvel blending transparency with illuminated elegance for thrill and romance alike.

Known as the crystal glass bridge, it spans the wide waters of Rong Lake in this open pedestrian park, designed as a modern marvel blending transparency with illuminated elegance for thrill and romance alike.

Visitors cross its sleek deck amid the musical fountain’s spray and nearby pavilions, often pausing midway to capture the surreal double world of lake and sky. Free to wander as part of the lakeside paths, it connects promenades under ancient banyans, making it a effortless highlight for sunset strolls or midnight confessions, where the city’s pulse fades into whispered waves.

It had been a beautiful warm evening in Guilin, but now The Wandelgek returned to his hotel because already tomorrow he would travel further into this wonderful area …