27. China/Guangxi: Boat tour on the Lijiang or Li River to Yangshuo (Lijiang River Scenic Zone (UNESCO World Heritage Site))

A difficult night

The Wandelgek had been sound asleep for a while but around 4 AM he woke bathing in sweat and not feeling well at all. Then started a difficult 2nd half of the remaining night of which I’ll spare you the details, but it left him totally exhausted and empty and not feeling well at all. It appeared to be a classic case of food poisening. The strain of luck regarding food poisening had ended after being a bit careless in choosing a restaurant last evening in Guilin. This carelessness was probably caused by his growing appetite and the fact that he had not had food poisening while travelling since 1999. In that year he had been gambling with his health when he ordered a dish of horse meat in Kathmandu, Nepal. It meant a whole day in bed next day, fever and everything else that comes with food poisening. It took two more days to get a bit more strength and it meant skipping the plan to drive to Pokhara and do a walk there.

This morning was bad too. The Wandelgek tried to drink and eat a bit, but that did not go well. Luckily he did feel well enough to leave the bed and he did not have a fever. This meant he could travel.

Boat tour on the Li River

He slowly started feeling better when he boarded the boat for the boat tour he had planned on the Li River, but he still needed to stay in the vicinity of the toilets. Luckily the sun shone brightly and this made him feel a bit better during the boat tour.

A classic Li River boat tour from Guilin to Yangshuo is a half‑day downstream cruise through limestone peaks, small riverside villages, and terraced fields, ending near the lively old town of Yangshuo.

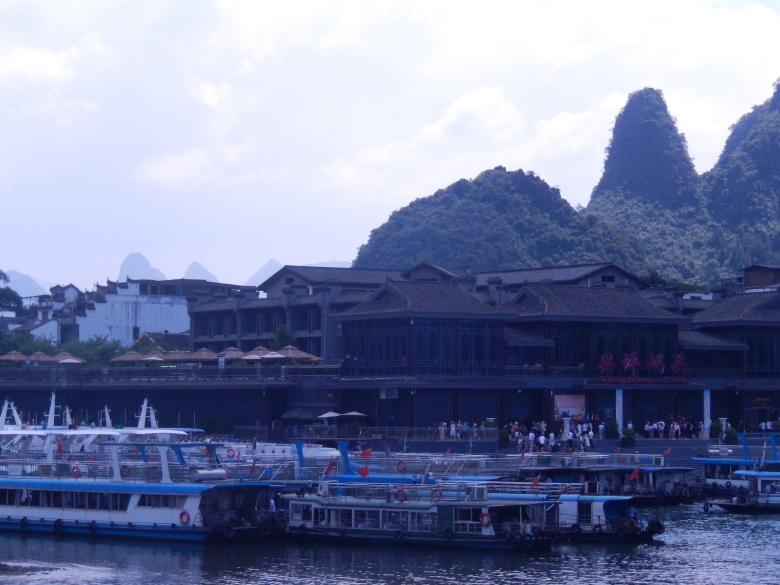

Boats depart from quays southeast of Guilin (commonly Mopanshan or Zhujiang piers) and follow the river about 80 km to Yangshuo. The cruise usually takes 4–5 hours, with morning departures around 9:00–9:30, arriving around early to mid‑afternoon.

Standard tourist boats have indoor seating with large windows and open decks where you can stand outside to photograph the scenery and feel the breeze.

Depending on the vessel class, a simple Chinese lunch or a buffet meal is served on board, so most of the journey is spent relaxing, eating, and moving between the cabin and viewing decks.

Along the banks you pass bamboo groves, sandbanks, and patches of farmland where water buffalo, fishermen, and villagers appear and disappear as the boat glides by…

Beneath is a map of the Li River area between Guilin and Yangshuo, where the light green line on top of the blue river, indicates the boat tour starting at Mopanshan or Zhujiang piers and ending at Yangshuo.

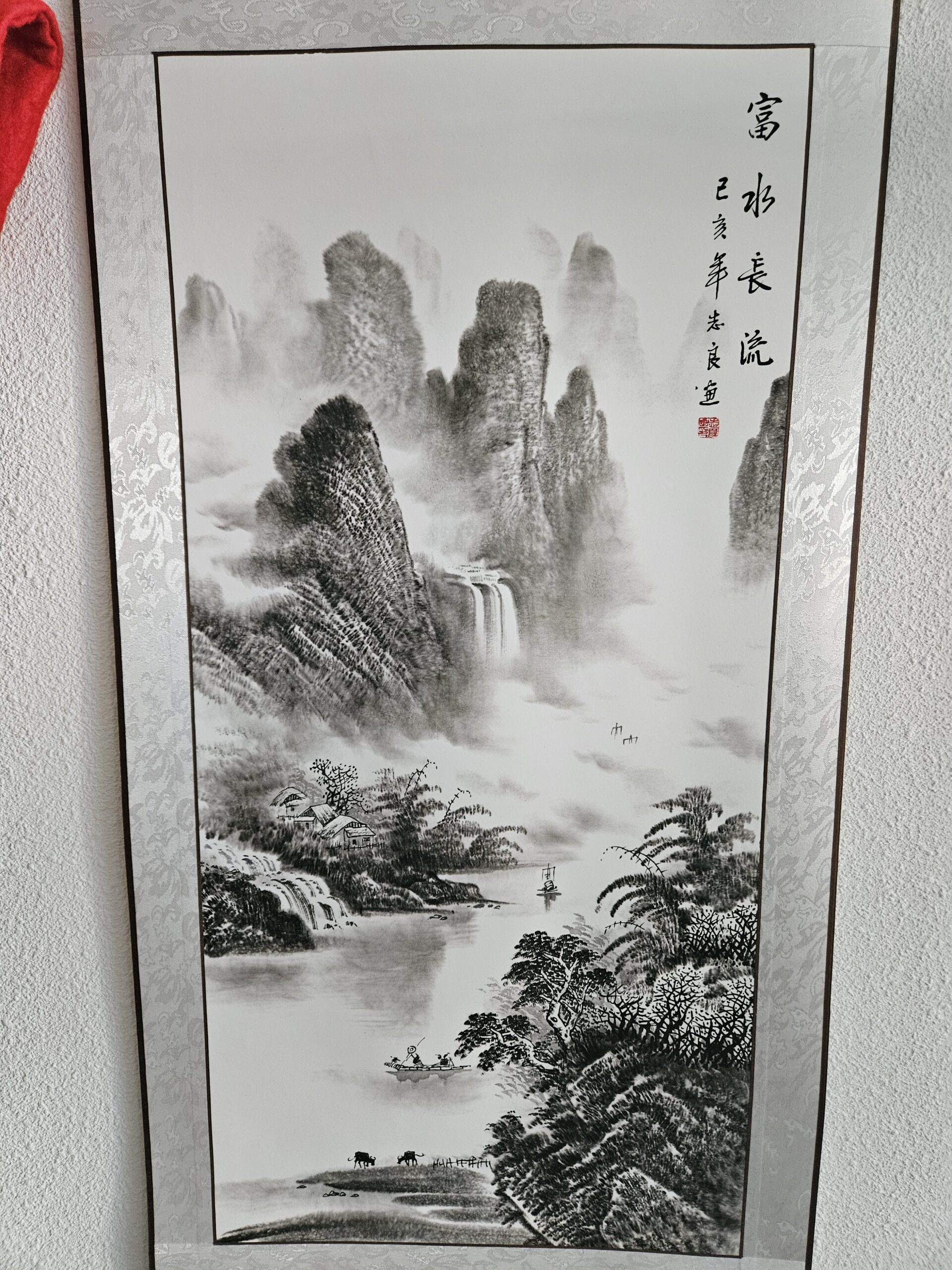

The river winds between steep karst mountains, giving long views of solitary peaks, cliffs, and narrow gorges that inspired many traditional landscape paintings, like the one The Wandelgek bought in Guilin, which now decorates his living room:

These painted peaks and the river dreamily floating through, are idealized visions of a landscape which remarkably much resembles those visions.

These painted peaks and the river dreamily floating through, are idealized visions of a landscape which remarkably much resembles those visions.

The Wandelgek and the River of Painted Peaks

And so my boat ride into a painting started…

The morning sun shone bright and almost unclouded above the quay south of Guilin. The river below sparkled like liquid glass, each ripple catching the light and scattering it in flashes of jade and silver. The Wandelgek stepped aboard his boat, his heart already stirred by the gleam of day. The peaks around him rose crisp and green against a blue-ish sky, and he felt as though the heavens themselves had opened to reveal a painted world.

As the vessel glided from the pier, the air filled with the scent of warming stone and blossoming reeds. A soft wind brushed his face while the boat’s prow cleaved the sunlight-dappled current.

As the vessel glided from the pier, the air filled with the scent of warming stone and blossoming reeds. A soft wind brushed his face while the boat’s prow cleaved the sunlight-dappled current.

The river widened and curved into a valley blazing with color: bamboo leaves flashing emerald, terraced fields gleaming yellow with ripening rice, and sky as blue as new porcelain. The hills rose taller, crag sharp and sheer, their shadows short and moving slowly across the swirling reflections. Folded Brocade Hill shone ahead, each layer of limestone glowing a different shade of ochre, as though the mountain wore robes of silk stitched by the gods.

The river widened and curved into a valley blazing with color: bamboo leaves flashing emerald, terraced fields gleaming yellow with ripening rice, and sky as blue as new porcelain. The hills rose taller, crag sharp and sheer, their shadows short and moving slowly across the swirling reflections. Folded Brocade Hill shone ahead, each layer of limestone glowing a different shade of ochre, as though the mountain wore robes of silk stitched by the gods.

Imagine drifting down the Li River at dawn under a partly cloudy sky, with plenty of sun gilding the emerald waters and karst towers that pierce the horizon like dragon spines—limestone monoliths sculpted over 20 million years by relentless, acid-laced rain into Yangshuo’s iconic fenglin pinnacles.

Hidden Caves & Riverine Labyrinths

Slip into Crown Cave’s 12 km underworld: stalactites weep like chandeliers, underground rivers roar past waterfalls in echoing vaults, birthing a subterranean pulse. Nearby, Reed Flute and Qixing glow with iridescent crystals under colored lights, while the Li’s 83 km serpentine course carves gravel terraces and braided tributaries, mirroring the sky in its glassy bends.

Epic South China Karst Saga

Guilin’s spectacle anchors the colossal South China Karst—500,000 km² of fengcong hill clusters and towers sprawling from Shilin (Yunnan) north to Wulong (Chongqing), plunging south through Guangxi into Vietnam’s Tam Coc karst gorges and Ha Long Bay’s 1,600 limestone islands—a 300+ km geomorphic epic transcending borders.

Surrender to karst magic: where rain devours stone like alchemist’s brew, forging sinkholes, poljes, and peaks that defy time—pure adrenaline for geology-loving wanderers.

Karst is a unique landscape shaped by water slowly dissolving soluble rocks like limestone over thousands or millions of years. Rain picks up carbon dioxide from the air and soil, turning slightly acidic, then seeps into cracks in the rock, widening them into caves, sinkholes, and underground rivers.

How It Forms

Water acts like a weak acid (carbonic acid) that eats away at limestone or dolomite, creating jagged peaks, deep pits, and hidden tunnels instead of normal rivers and valleys. This happens fastest in rainy areas with fractured bedrock, leaving few surface streams since water drains underground.

The process starts small—at cracks—and grows into dramatic features like those near Guilin, where tower-like hills rise sharply.

Key Features

- Sinkholes (dolines): Bowl-shaped pits where the surface collapses.

- Caves: Vast chambers with stalactites and stalagmites from dripping minerals.

- Disappearing streams: Rivers that vanish into the ground, reappearing as springs.

Everyday Impact

Karst covers about 20% of Earth’s land and stores vital groundwater, but it’s fragile—pollution spreads fast through caves, and building risks collapses. Examples include Guilin’s fenglin towers and Vietnam’s Ha Long Bay limestone islands from the same South China Karst system.

At Nine Horse Fresco Hill, the sun transformed the cliffside into a vast golden relief. The Wandelgek shaded his eyes to follow the dark mineral streaks — horses mid-gallop, manes lifted by wind unseen.

The boatmen laughed, urging everyone to count them. “Nine? Ten? Perhaps eleven if your heart is lucky!” He counted again and again, each time discovering one more head, one more shape. “The horses,” he wrote in his notebook, “run not upon stone, but through the imagination of those who still believe in miracles.”

All along the banks, the day shimmered. Fishermen guided bamboo rafts through slow-moving eddies, their cormorants darting like living shadows in the sunlight.

Children waded in clear shallows, laughing as they filled baskets with drifting lotus petals.

Water buffalo grazed lazily under the bright expanse of sky, their wet backs gleaming like polished bronze.

The air was thick with dragonflies, flashing sapphire and gold.

By afternoon, the landscape burst into an almost unreal radiance.

The peaks drew closer, cradling the river in a procession of emerald spires.

Some of the karst hills and cliffs have names associated with painting, like e.g Pen heak peak, Painting brush hill and Painted cliff…

The mountains on the Chinese 20 yuan note are the karst peaks along the Li River near the small town of Xingping, close to Yangshuo in Guangxi, southern China. These are classic limestone towers formed over millions of years by erosion and dissolution in a humid subtropical climate.

The scene on the banknote shows a bend in the Li River near Xingping, in the Guilin–Yangshuo section of the river in Guangxi Province. This stretch is sometimes called the “20 Yuan View” or the “Reflection of Yellow Cloth Shoal,” a calm, shallow section where the clear water reflects steep green hills. Karst mountains and geology. The mountains are limestone karst towers: steep, craggy peaks created as slightly acidic rainwater dissolved thick carbonate rocks over time, leaving behind isolated hills. Continuous erosion, sinkhole development, and river incision shaped the landscape into sharp cones and ridges that rise abruptly from the river and surrounding fields. Cultural and artistic significance. The Li River and its hills have long inspired Chinese painters and poets, who depict the misty peaks, winding water, and small boats as symbols of an ideal, harmonious landscape. Putting this view on the 20 yuan note highlights it as one of China’s emblematic sceneries, much like a visual shorthand for “picturesque rural China.”

The exact “20 yuan” viewpoint

The note’s composition matches a viewpoint along the Li River just outside Xingping, where the river makes a broad curve framed by several distinctive cone-shaped peaks. The classic view combines three elements: the sweeping bend of the river, a foreground with a fisherman on a bamboo raft, and layered karst hills fading into the distance.

Visiting the area today

Nowadays travelers usually reach the scene by boat trips along the Li River between Guilin, Yangshuo, and Xingping, sometimes stopping specifically to line up the note with the real landscape. Nearby hills such as Laozhai Mountain above Xingping offer higher vantage points, where the same karst towers and winding river appear like a traditional ink painting from above.

Wben you’re feeling not too well, a day like this, relaxing on a boat on the sun works marvelously well for recovery, but it was not enough to recover completely from the food poisening. I decided I needed a day of rest the day after …

Yangshuo

As the boat entered the last bends toward Yangshuo, the town appeared amidst orchards and fields, roofs glinting like silver tiles beneath the late sun. On the banks, market stalls glowed with hanging red banners, and a flute’s melody drifted faintly across the water. The Wandelgek set his pen down at last, knowing that prose—and even poetry—could scarcely capture a day so vivid and alive.

Boats dock at a quay on the edge of town (such as Longtoushan or Shuidongmen), from where it is a short walk or quick cart ride into Yangshuo’s central streets, cafés, and riverside promenade.

When he stepped ashore, the river sparkled behind him one last time. The peaks stood sharp and eternal in the blazing light, and the Li flowed on—golden, laughing, and full of stories. For The Wandelgek, it was not farewell but promise: that brightness like this, once seen, would forever illuminate his wandering path, because:

“Not all who wander are lost” ;-).

Quote by J.R.R. Tolkien