Citywalk 1: Brussels according to François Schuiten: Palais de Justice (Palace of Justice / Paleis van Justitie)

After leaving the Louiza tubestation, The Wandelgek’s staring eyes were drawn by this humongous, colossal building. It was the Palace of Justice and the name Palace couldn’t have been more fitting…

Palais de Justice

Exterior

The Wandelgek had arrived at the rear side of the palace and decided to walk around …

Now the first thought this building immediately invokes is: “THIS IS REALLY BIG!!!”.

It was somehow inescapable to not see this building. It even reflected in the windows of bordering modern office buildings and somehow it seemed too large to be captured on camera as a whole …

The Palace of Justice of Brussels or Law Courts of Brussels is a courthouse in Brussels, Belgium. It is the country’s most important court building, seat of the judicial arrondissement of Brussels, as well as of several courts and tribunals, including the Court of Cassation (Belgian supreme court), the Court of Assizes (highest criminal court), the Court of Appeal of Brussels (appellate court), the Tribunal of First Instance of Brussels (general jurisdiction), and the Bar Association of Brussels.

Designed by the architect Joseph Poelaert, in an eclectic style of Greco-Roman inspiration, to replace an older courthouse, the current building was erected between 1866 and 1883. With a ground surface of 26,006 m2 (279,930 sq ft), the edifice is reputed to be the largest constructed in the 19th century and remains one of the largest of its kind. The total cost of the construction, land, and furnishings approximated 50 million Belgian francs. The building suffered heavy damage during World War II, when the cupola was destroyed and later rebuilt higher than the original. The structure has been under renovation since 1984 and scaffolding from that era still hangs on the building, though it is set to come down by 2030.

The building stands on top of a hill, overlooking the poorer quarters of the Marollen (which I will visit in Walk 2), but is best described as being a hill itself.

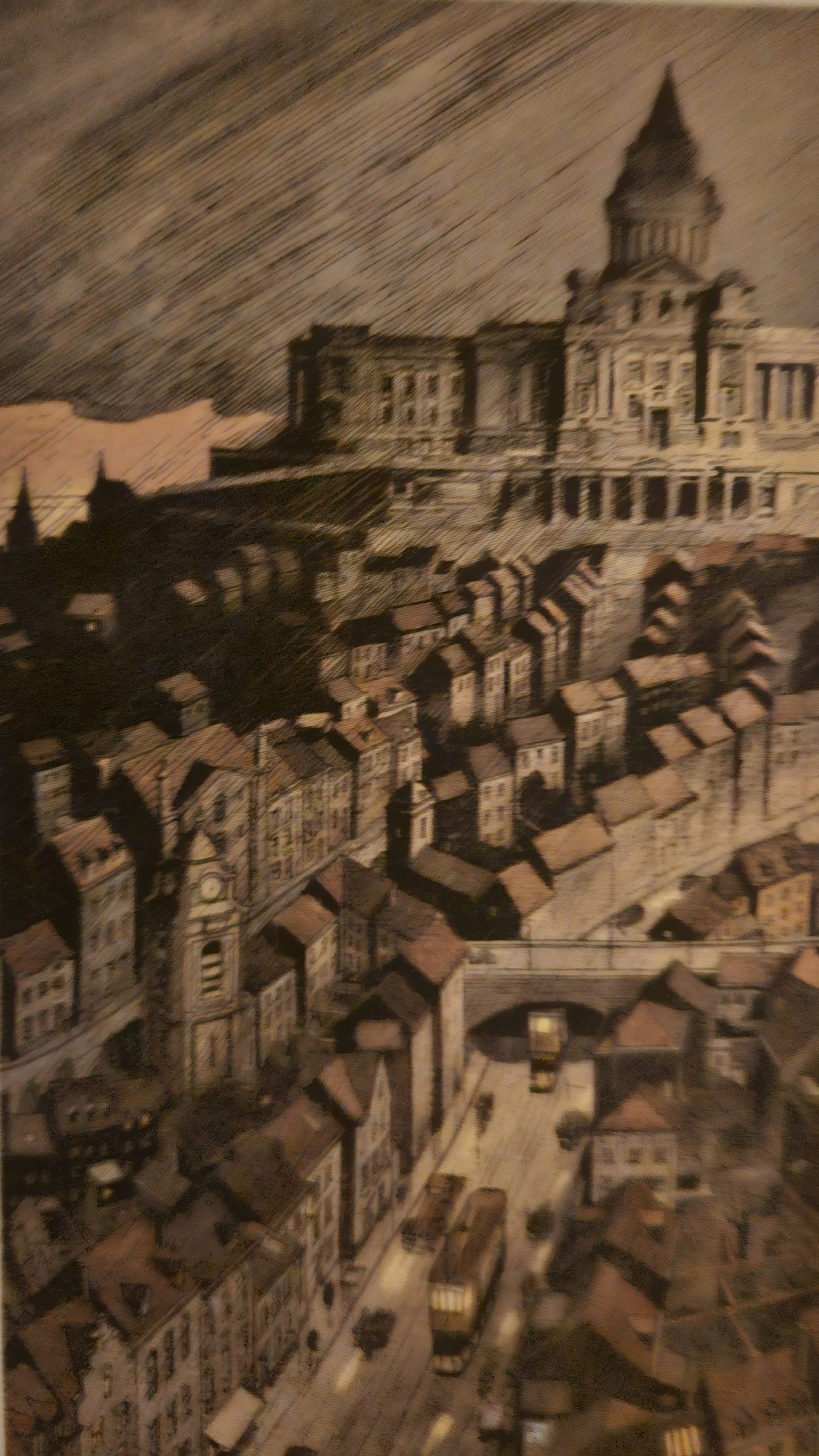

So why visit this very impressive building first of all other attractions of this town? Because it plays a pivotal part, almost that of a character, in the Obscure Cities books of François Schuiten.

Benoit Peeters describes it as an omnipresent, can’t be overseen, too large for its purpose, too oversized to belong in Brussels, never finished building which acts as a hidden passage way from our world to the Obsure World and has an even more impressive and finished in every detail companion building in the Obscure City of Brüsel.

François Schuiten depicted it as this humongous, colossal giant, which leaves people looking at it, utterly awe struck and perplexed. The building not just appears in his Obscure Cities books, but has escaped from those narrow confinements into his works for Blake and Mortimer, his works about Brussels (obviously) and many stand alone posters or drawings. Not just the exterior, but the interior as well.

When you stand before the Palace of Justice in Brussels, you are not simply facing a building—you face a paradox, a mountain of stone that is both oppressive and liberating. Step inside and you enter a labyrinth where scale overwhelms the human body. The vast corridors, gilded halls, staircases that climb endlessly into shadow—all conspire to disorient. It is as if the architects sought not to serve justice, but to construct a ritual of passage.

So this just had to be my starting point for this undertaking.

The entrance at the Place de Poelaert was under construction and there was some scaffolding, looking like matchsticks among the huge entrance pillars.

The Wandelgek was awestruck after his walk around the Palace and after walking through this larger than life collonade into the Palace, but still he was not prepared enough for what he would find and experience there. It made complete sense afterwards, why Schuiten and Peeters had chosen this building to have such a pivotal role in their Obscure Cities books…

Interior

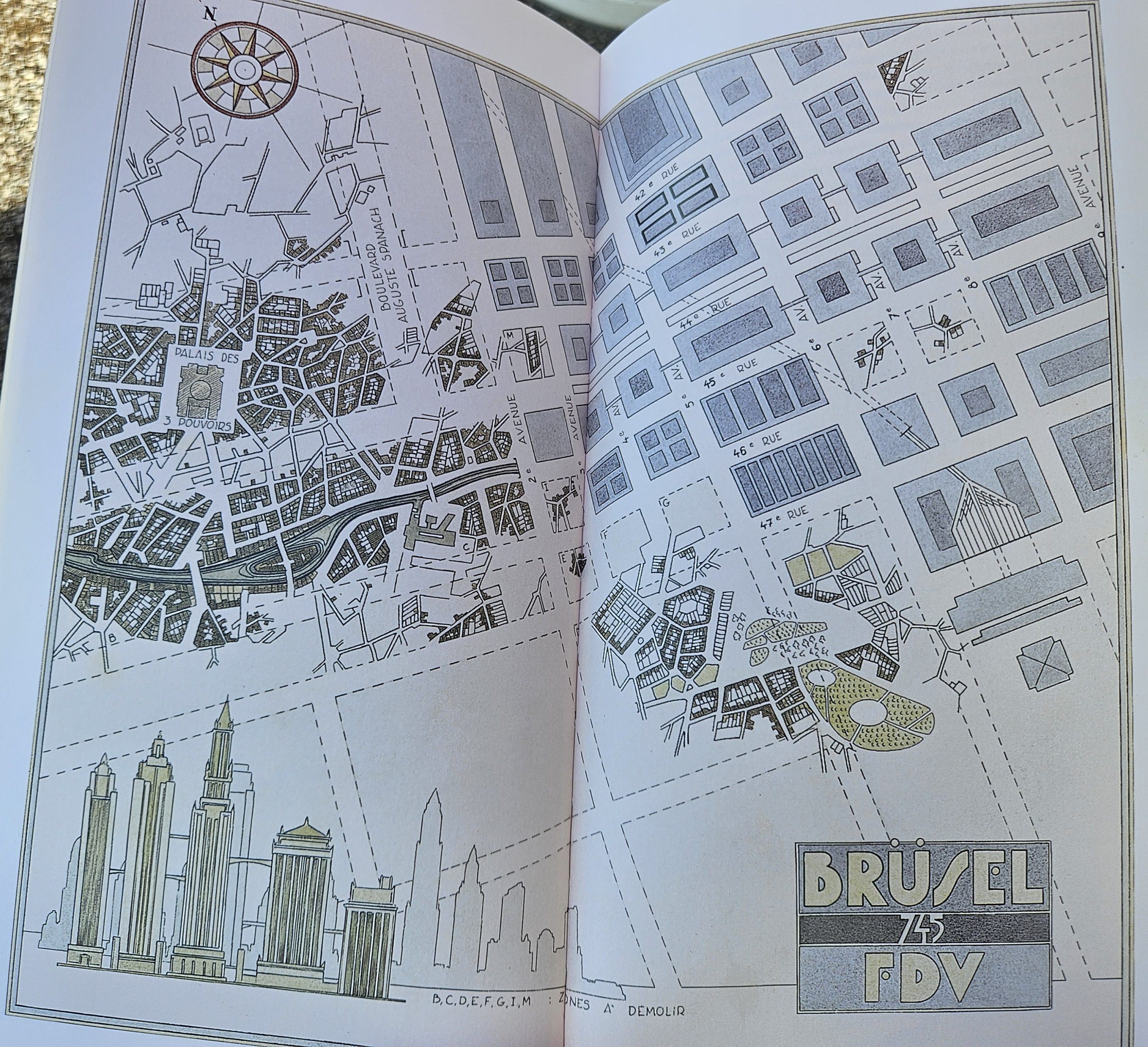

In the Obscure City of Brüsel, the Palace has a twin sister named The Palace of the three Powers. It is topped by a piramid instead of a dome, which was Poelaert’s original idea.

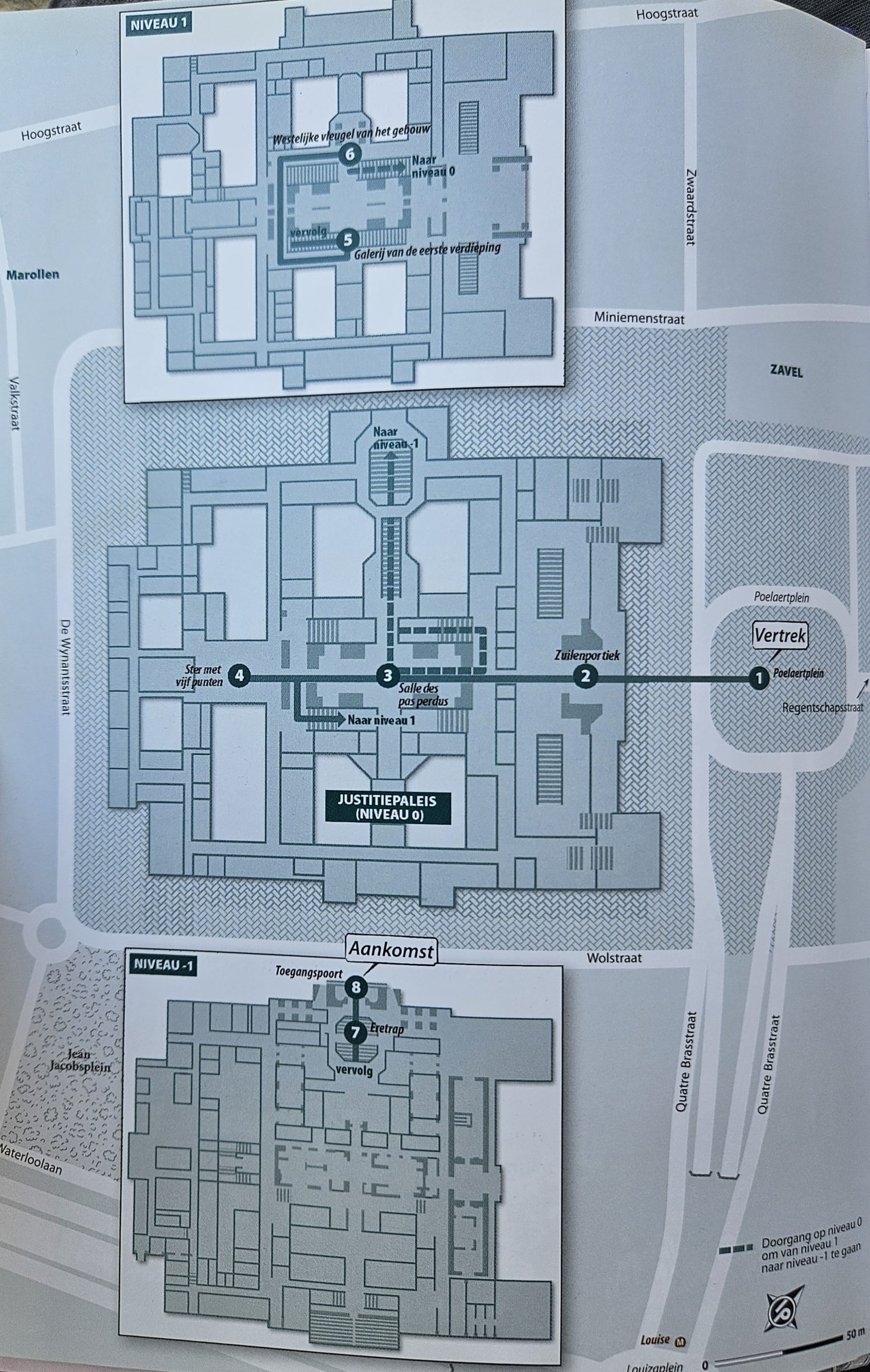

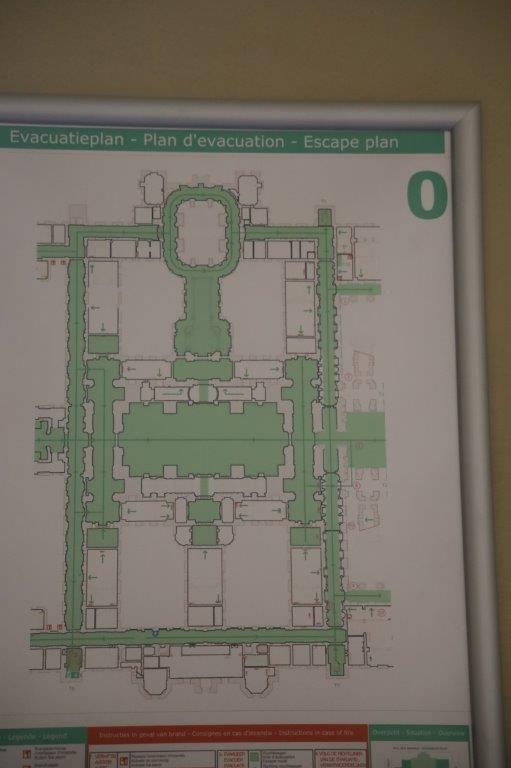

Map

The Palace’s main hall is humongous and is bordered by galleries of huge pillars …

Walking though those interminable galleries, The Wandelgek felt that the walls echo differently depending on where you stop; some corners seem to swallow sound, others amplify it until it is unbearable. Light filters through high windows, rare, distant, as though it were already passing into another atmosphere.

One feels suspended in time.

It is within these disorienting shifts of scale and perspective that the link to the Obscure World reveals itself. You must not think of the Palace as only a civic monument; you must think of it as a hinge. Its sheer weight presses our reality against another reality, until fissures appear. The great dome is not only a roof but a lens, a vessel for perception. In certain chambers, if you are attentive, the geometry misaligns—arches open onto stairways that no longer correspond to the building’s plan. That is where the transition begins.

For the inhabitants of the Obscure Cities, the Palace is like a lighthouse: a point of orientation from afar, a place where their world and ours skirt the surface of one another. Judges, lawyers, and defendants hurry past it daily without suspecting. But for those who see differently, who feel the tremor in the air, these colonnades become corridors of initiation.

To pass through the Palace toward the Obscure World is not a matter of secret doors, but of perception. A misstep, a sudden silence, the glare of a shaft of light at the wrong time—and the echo of your own footsteps begins to lead you elsewhere. You look back, and the Brussels you knew has softened into another geometry, another destiny.

For me, the Palace of Justice will always remain both terrifying and sublime: a colossal machine designed—knowingly or not—to tear open the fabric of reality, offering us a glimpse into the strange, vertiginous beauty of the Obscure.

In reality it was also literally a vast tool to impress, leave awestruck and above all frighten the citizens of The Marolles into submission toward the powers that rule.

Beneath is an example of a courtroom still in use nowadays for judgements …

The construction of the Palace of Justice in Brussels was a monumental event, but it came with a heavy cost for the inhabitants of the Marolles neighborhood. To clear space for the Palace, a sizable section of the district was demolished—over 600 houses were razed, displacing hundreds of residents. While compensation and new homes were offered to some, many were forced into smaller, cramped dwellings far from their original community, disrupting tight-knit local bonds and daily life.

After having seen the exterior and interior of the Palais de Justice I could only describe this as an full force exercise in Absurdism …

Then… and only then, The Wandelgek noticed the Palais de Justice was standing in front of a huge Square, the:

Poelaertplein (Poelaert Square / Place de Poelaert)

Poelaert Square (Place Poelaert / Poelaertplein) is one of Brussels’ most impressive public spaces, located directly in front of the monumental Palace of Justice. Named after Joseph Poelaert, the architect behind the palace, this vast square serves as a dramatic urban stage perched high above the city, marking the boundary between the elegant Louise district and the historic, vibrant Marolles neighborhood.

Historically, Poelaert Square’s development was closely tied to the construction of the Palace of Justice in the late 19th century—a process that dramatically transformed the area and left an enduring architectural mark on Brussels

Right on the square stands the Belgian Infantry Memorial, designed by Edouard Vereycken and inaugurated in 1935. This monument pays tribute to the Belgian foot soldiers who fought and died during World WarI and World WarII. It sits atop a raised platform overlooking central Brussels, embodying gratitude and remembrance for the infantry’s contribution. The inscription reads: “To the infantrymen who died for their country”

I have often found myself captivated by the enigmatic figure of Joseph Poelaert. In the world of the Obscure Cities, architects are as much dreamers as they are builders, and Poelaert stands at the crossroads of these two callings. Archticts are often called urbatects, which memeans they do not border their impact to 1 building or 1 city block or even a whole city quarter, but are allowed instead to design or redesign whole cities, often interiirs of buildings included. This creates cities which are drastically built after the example of one specific building style. He is not merely the creator of stone colossi; he is a conjurer of thresholds, a man whose vision ruptured the familiar streets of Brussels and opened a path to the unknowable.

Tourists flock here for the stunning panoramic views over Brussels; on clear days you can spot landmarks like the Koekelberg Basilica and the Atomium. The square itself is the largest in the capital—spanning about 750m²—which makes it ideal for sunset strolls, photography, and simply gazing at the city sprawled out below. Since 2019, a giant Ferris wheel called ‘The View’ has offered visitors a unique vantage point over the Belgian capital from 100m up.

From Poelaert Square, you can also use the free glass elevator that connects the upper and lower town—a direct route down into the Marolles, famous for its local markets and bohemian energy. The square borders notable war memorials and is always buzzing with city life, attracting both locals and tourists.

Poelaert’s essence lingers in the obsessions that define the Obscure Cities. His Palace of Justice is a monument not only to the law, but to the audacity of transforming urban reality. In our universe, he is admired and reviled—a visionary for some, a destructor for those displaced. In the Obscure Cities, where he build the Palace of the three Powers, such figures are almost mythic: those who dare to reshape cities, who court both chaos and wonder.

For me, Joseph Poelaert symbolizes the dangerous grace of architecture. His presence in the Obscure Cities is not just as a builder of palaces, but as a spirit who reminds us of the power—and the unintended consequences—of monumental ambition. Wherever the border between our world and the Obscure bends under the weight of stone and dream, you can sense Poelaert is never far away. Obsure city urbatects are more often like thatvand Eugen Robick (The Fever of Urbicande) is another fine example.

So this was the end of the first quite short walk including mainly the Palais de Justice and the Place du Poelaert.

Next The Wandelgek decided to walk toward the rear side of the Palais de Justice (Wijnantstraat) and took the Valkstraat (Falcon street) into the Marollen quarter.

See my next blogpost for my 2nd walk into the Marollen quarter.