Citywalk 3: Brussels according to François Schuiten: In search of rare François Schuiten publications and trying to get a glimpse of the Zenne river near Brussels South Railway Station

Going back to Les Maroles to score some Schuiten comic books

After an early rise, shower, breakfast and a cappuccino or two at the Place de la Liberté, The Wandelgek walked to Madoux tube station and returned to Louisa tube station, from where he returned by foot to the Vossenplein, to visit the comic book store and find some more rare François Schuiten books.

The comic bookstore was even surpassing my expectations based on its shopping windows …

The comic bookstore was even surpassing my expectations based on its shopping windows …

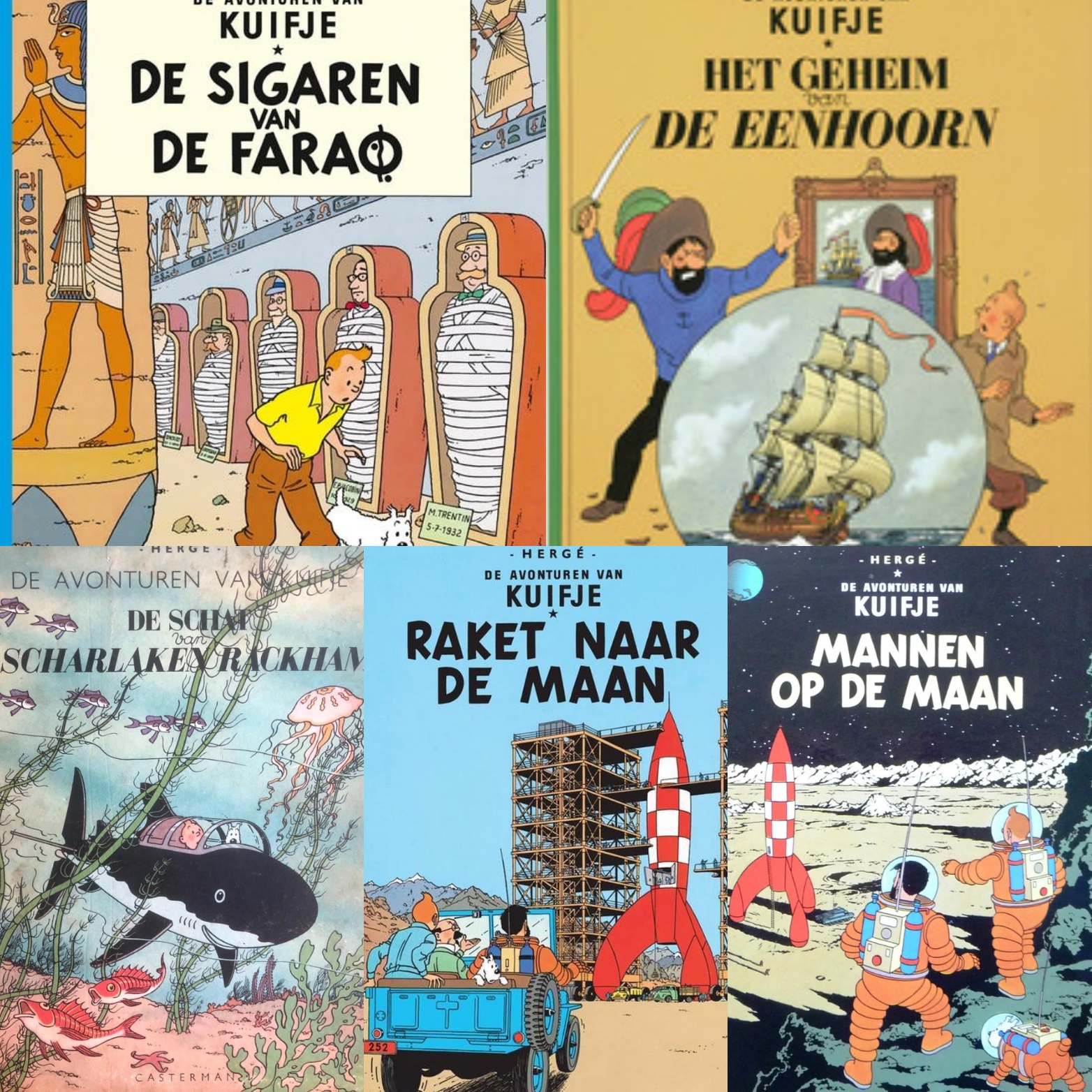

Tintin collectors items were present galore. The shark submarine from Treasure of Scarlet Rackham (De Schat van Scharlaken Rackham), ….

Tintin collectors items were present galore. The shark submarine from Treasure of Scarlet Rackham (De Schat van Scharlaken Rackham), ….

… the moon rocket from Rocket to the moon (Raket naar de maan) and Men on the moon (Mannen op de maan), the scale model of the Unicorn from The Secret of the Unicorn (Het geheim van de Eenhoorn) and the sarcophages from The Cigars of the Pharao (De sigaren van de Farao).

… the moon rocket from Rocket to the moon (Raket naar de maan) and Men on the moon (Mannen op de maan), the scale model of the Unicorn from The Secret of the Unicorn (Het geheim van de Eenhoorn) and the sarcophages from The Cigars of the Pharao (De sigaren van de Farao).

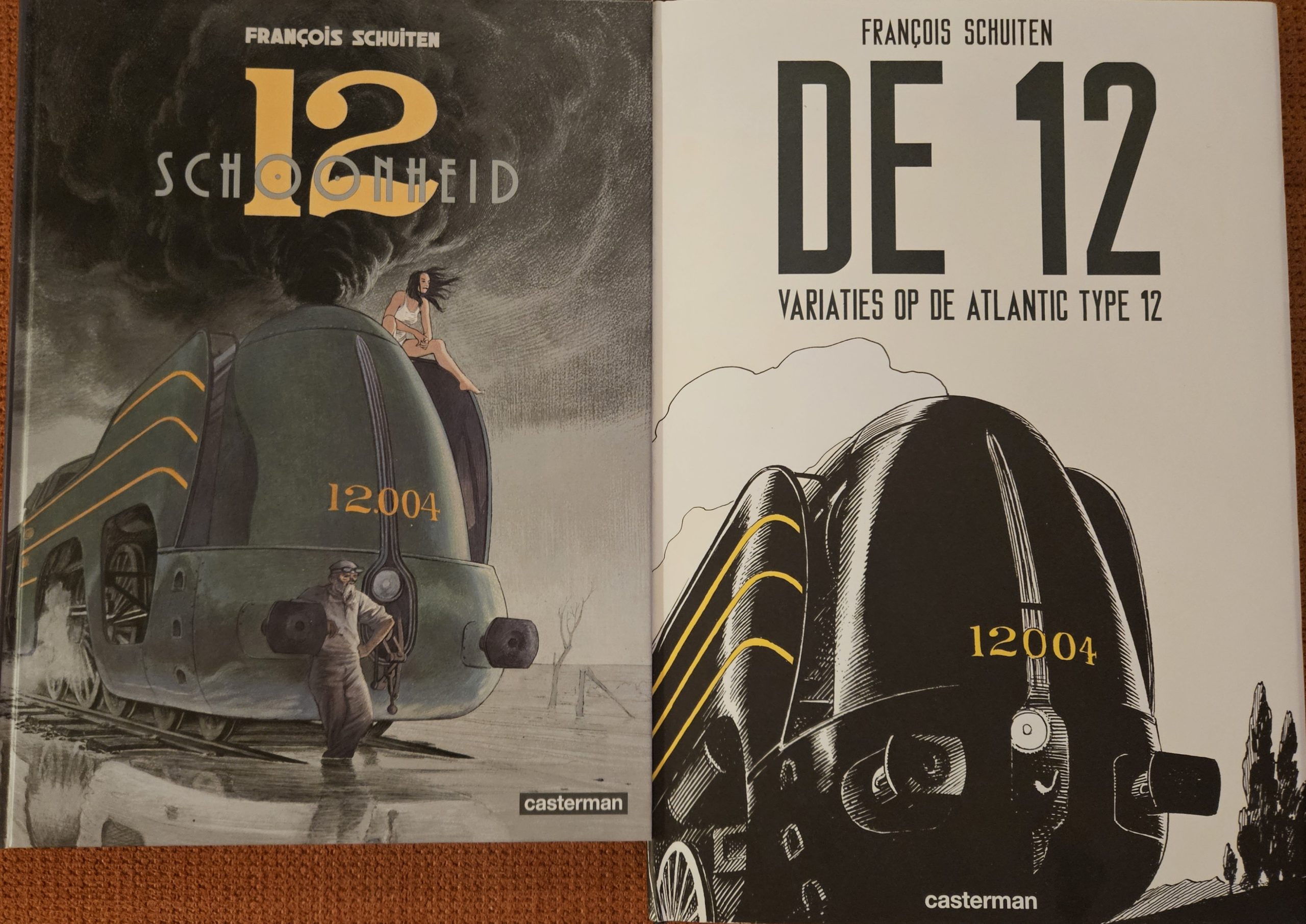

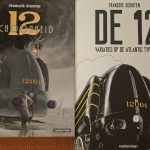

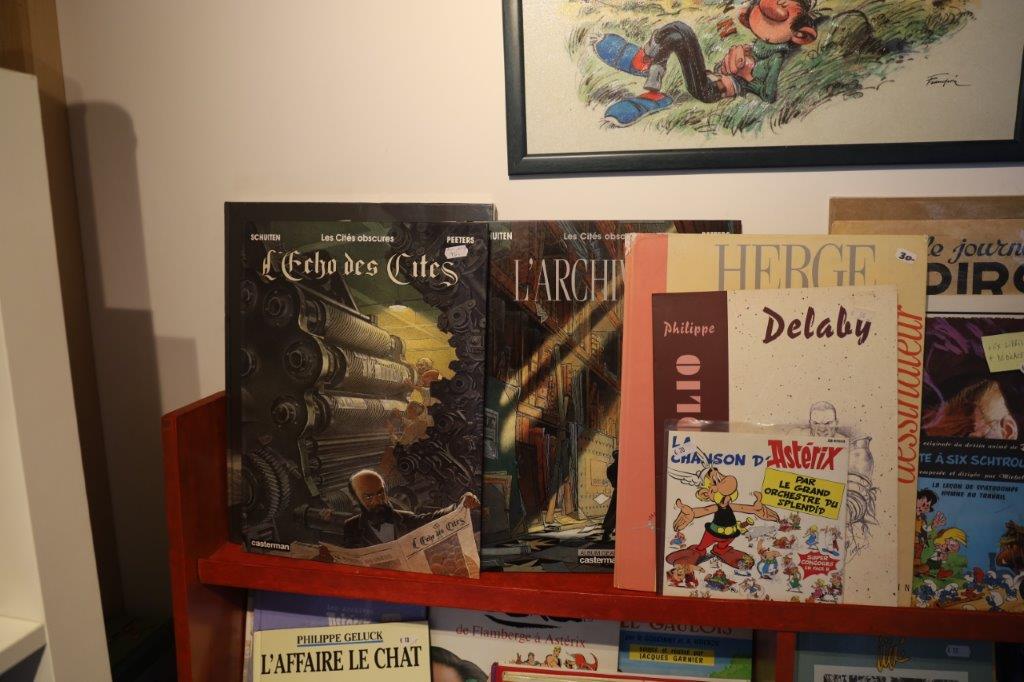

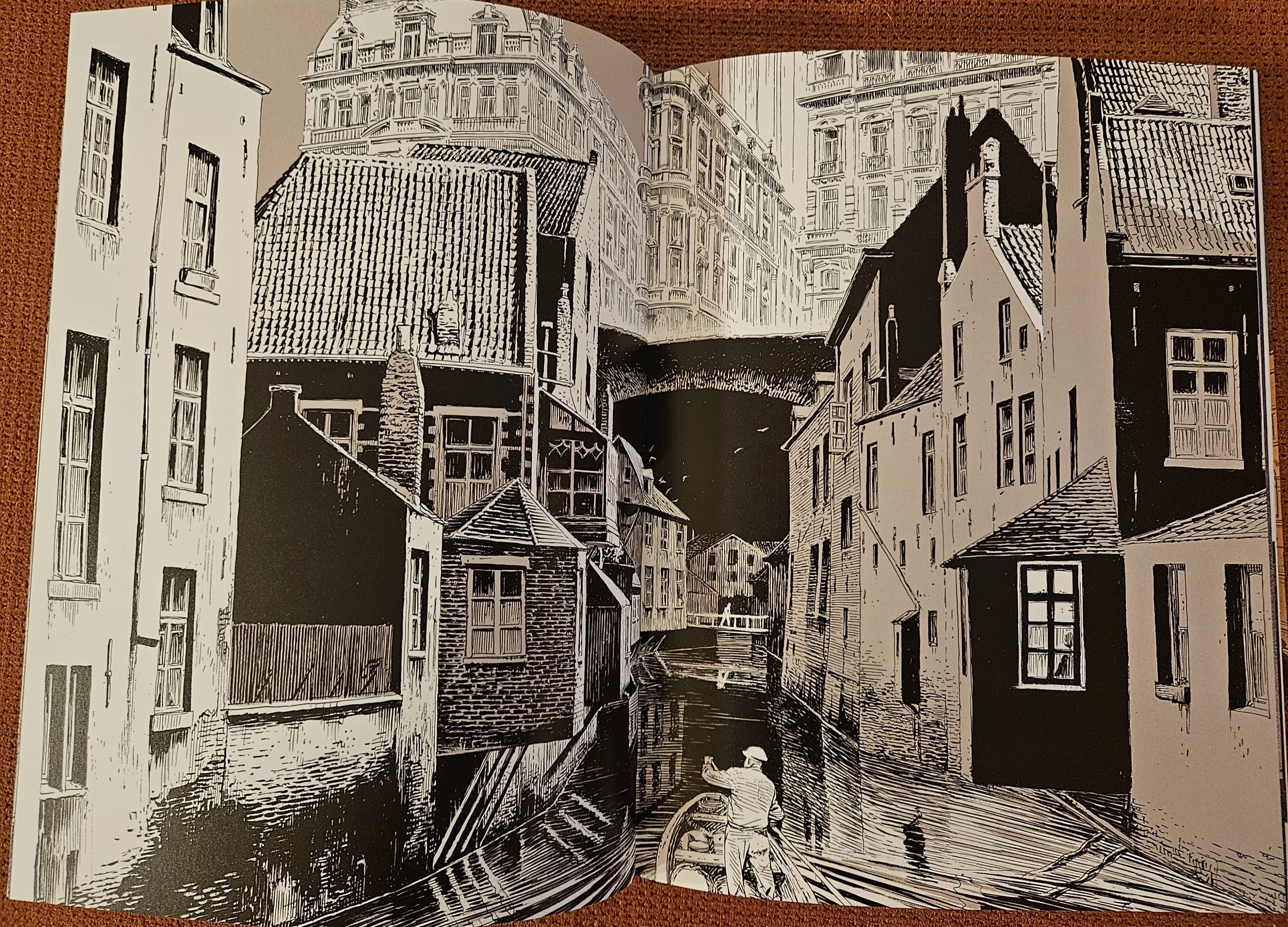

And then there were the enormous amounts of comic books and yes… also those created by François Schuiten.

And then there were the enormous amounts of comic books and yes… also those created by François Schuiten.

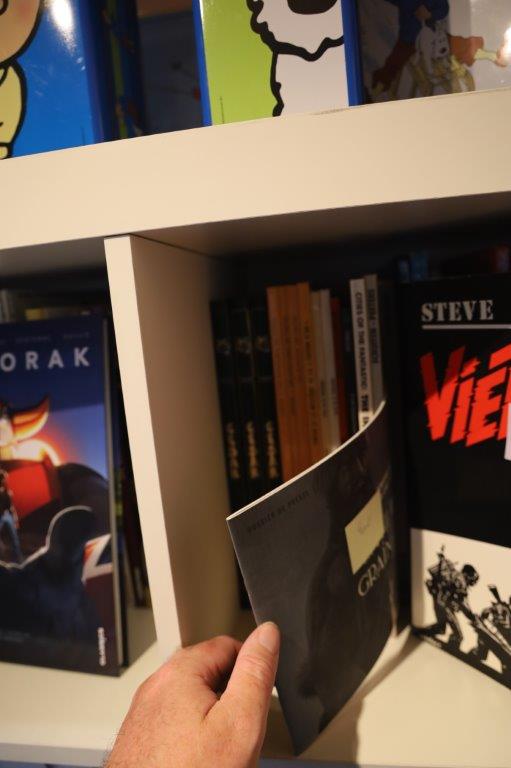

Luckily I found a very rare piece too. A press only publication for The Theory of the Sand Grain (De theorie van de Zandkorrel).

Luckily I found a very rare piece too. A press only publication for The Theory of the Sand Grain (De theorie van de Zandkorrel).

After buying some books and admiring the scale model of the Unicorn, The Wandelgek left for his next walk…

After buying some books and admiring the scale model of the Unicorn, The Wandelgek left for his next walk…

He returned to Louisa tube station and took the metro train toward Bruxelles-Midi (Brussel-Zuid), whichbis also a railway station…

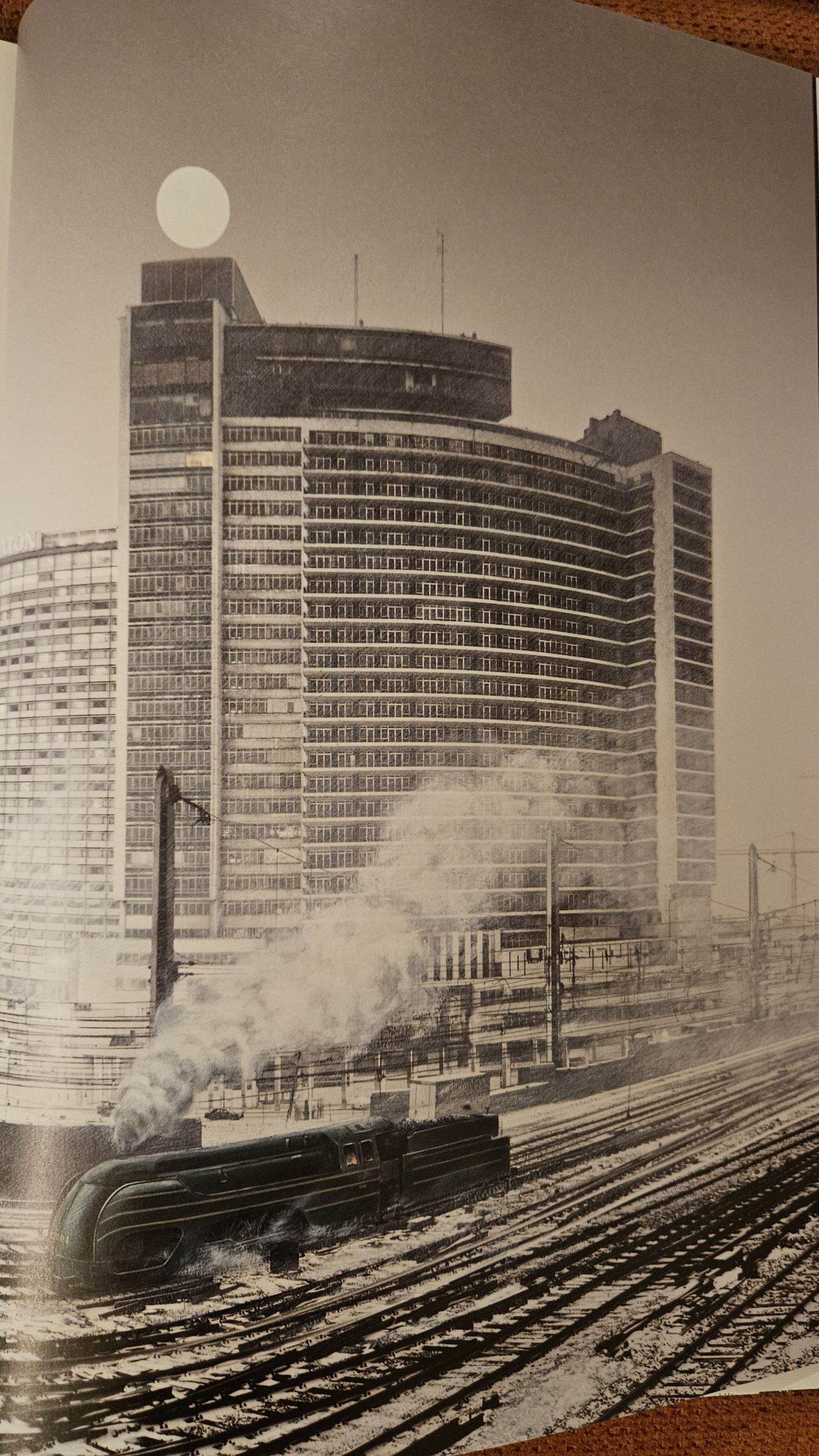

First he looked a bit at the area around the railway station and the railroad.

First he looked a bit at the area around the railway station and the railroad.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Brussels was served by two main railway stations: Brussels-North (opened in 1846) and Brussels-South (opened in 1869, replacing a nearby station of 1840). They are located just outside opposite ends of the Pentagon—an area within the ring roads which follow the boundary of the old city walls. Shortly after opening, both stations were handling large volumes of commuter, regional and international passengers, but through journeys required disembarking and a street-level transfer through the city’s old town, a distance of over 3 km (1.9 mi).

The idea of an underground railway line linking the two stations was first suggested in the 1860s, as part of a proposal for the covering of the Zenne, although it was never implemented. The current version was planned before World War II, after a decision originally made in 1909, and it came into service on 5 October 1952. Both stations were demolished and reconstructed to allow through services, reopening in 1952.

Three new intermediate stations were constructed along the route to serve the city centre. Two of them, Brussels-Chapel and Brussels-Congress, were intended stops only for local commuter services and have never been heavily used. The largest of the new stations, Brussels-Central, was built to additionally serve regional and international services transiting through Brussels. The combination of a city-centre location and numerous services to diverse destinations led to Brussels-Central becoming the busiest station in Belgium. Brussels-North, Brussels-Central and Brussels-South are now the three main railways stations in the city; they are also the three busiest stations in all of Belgium.

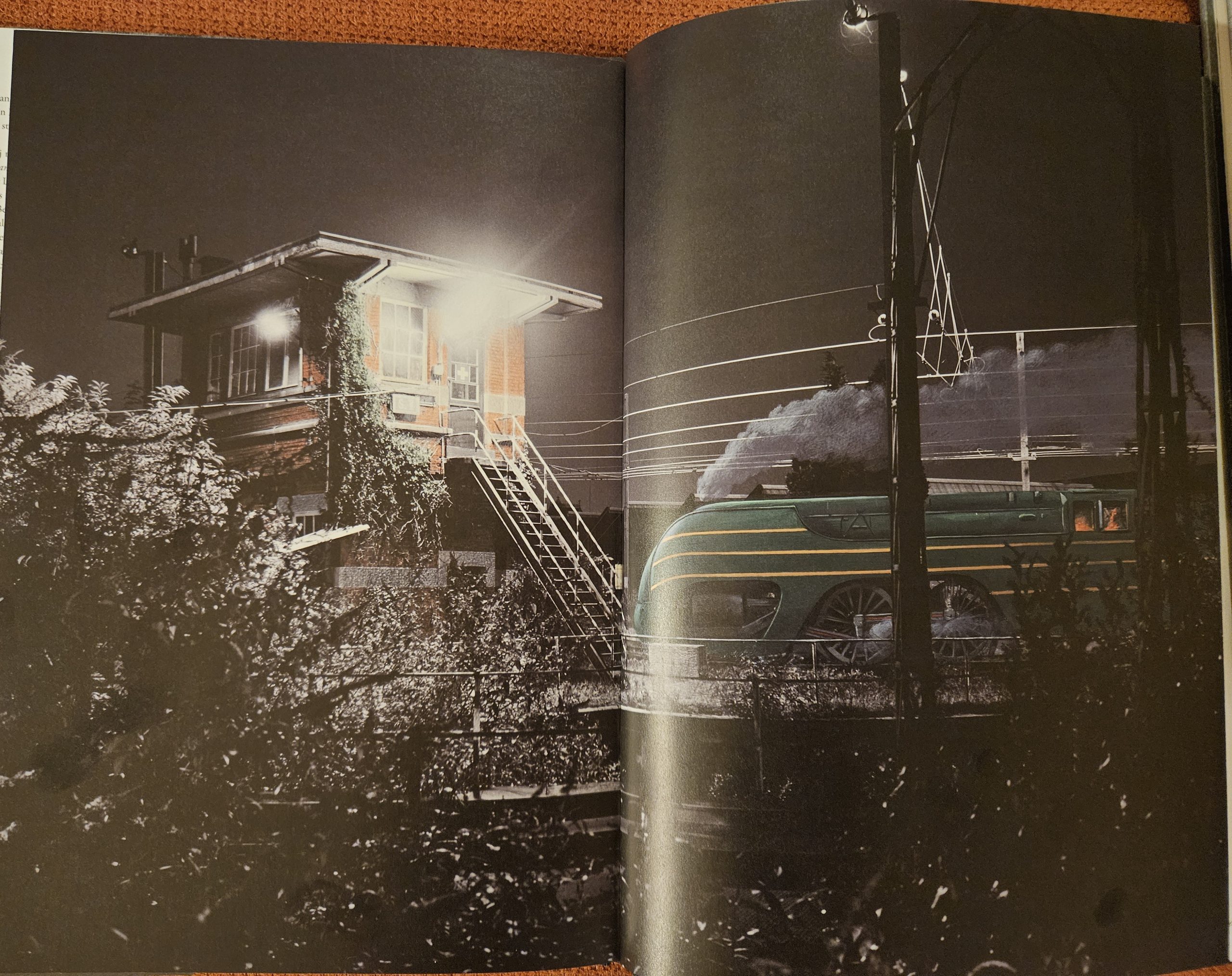

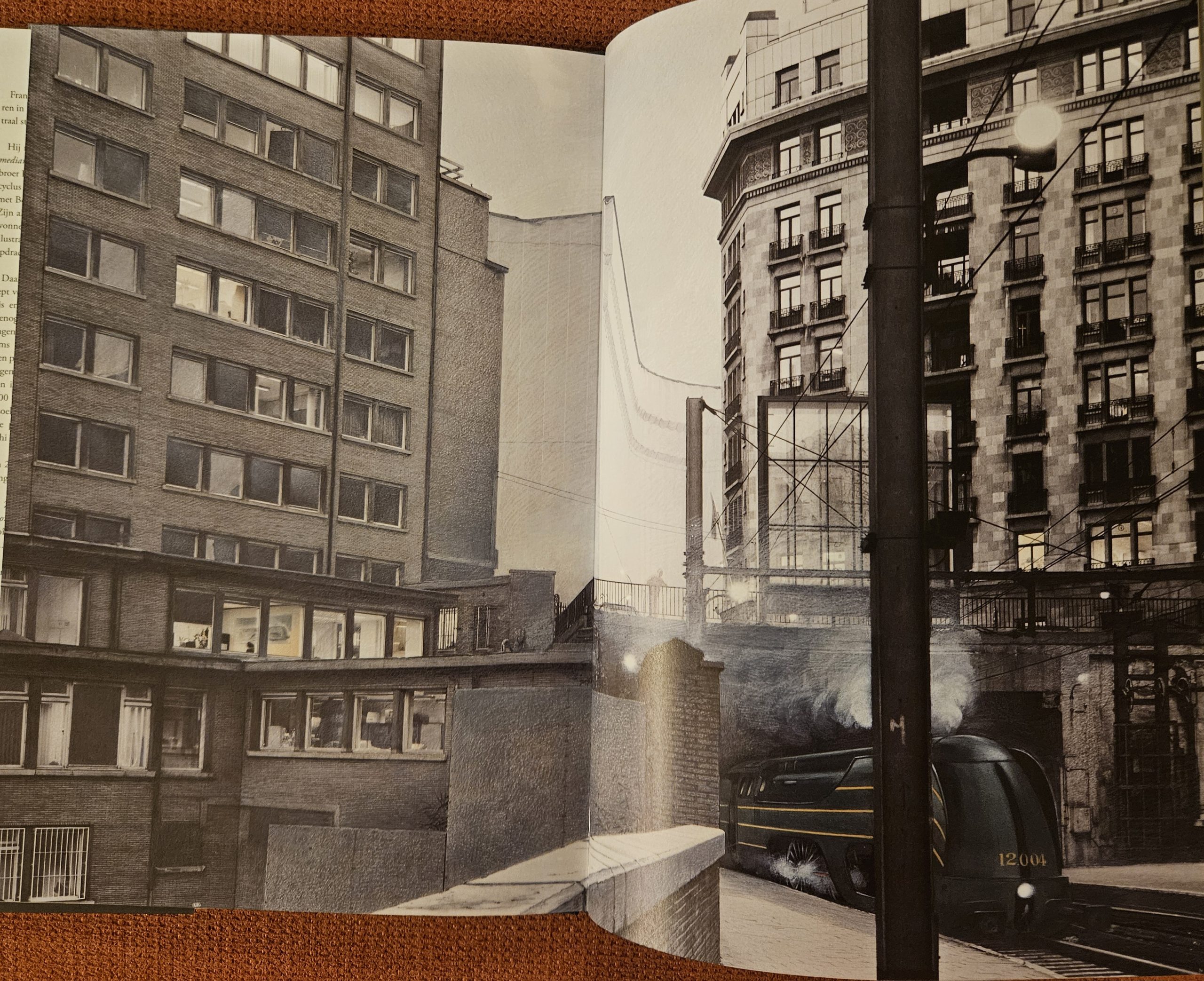

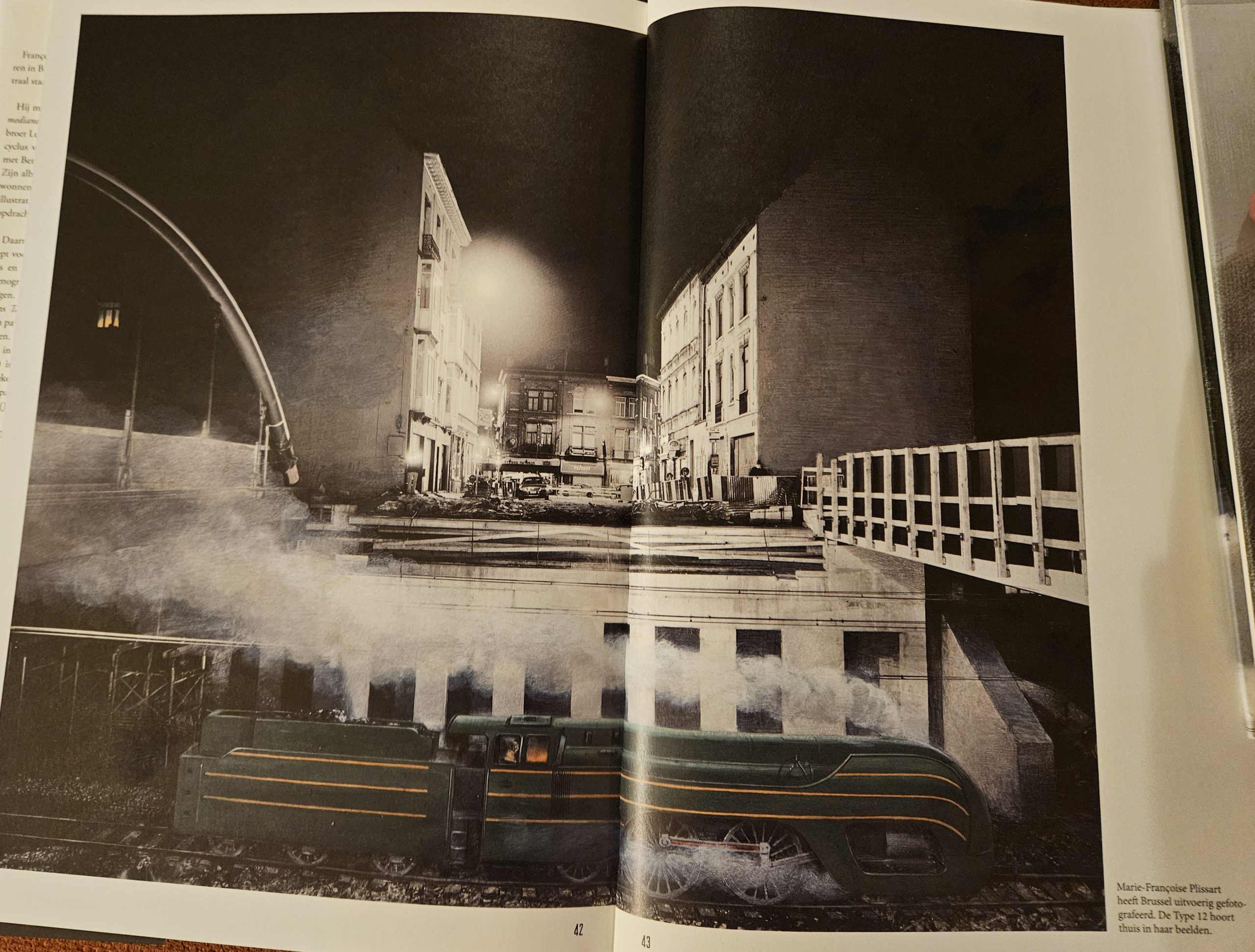

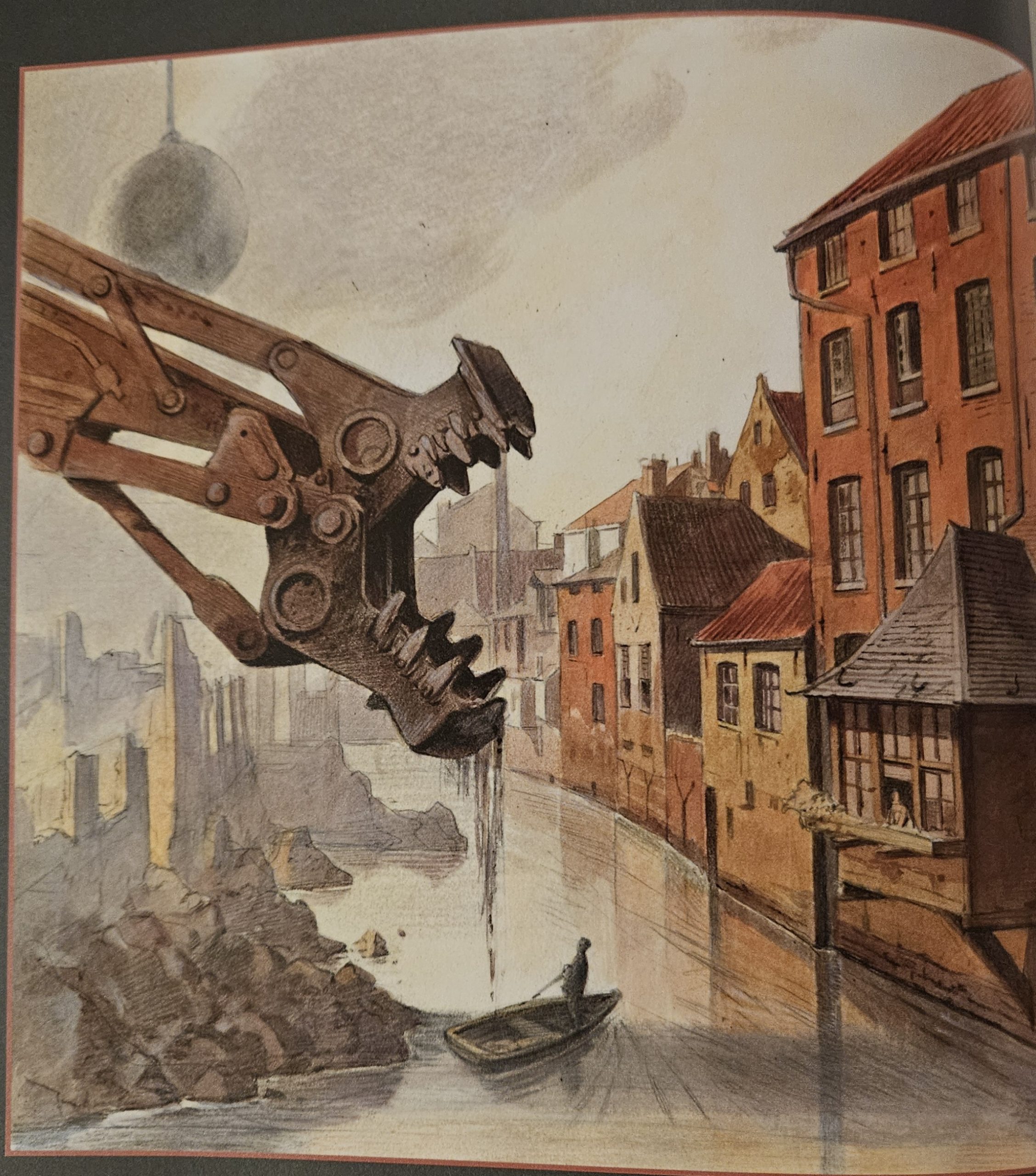

When one evokes the North–South connection carved through the heart of Brussels, one must imagine not only a railway but a gash, a deliberate intrusion into the living tissue of the city.

When one evokes the North–South connection carved through the heart of Brussels, one must imagine not only a railway but a gash, a deliberate intrusion into the living tissue of the city.

What was once a labyrinth of old streets, squares, and façades — modest yet stubbornly human — was torn away to create a monumental axis. This wound, at first raw and contested, grew into a kind of steel artery meant to accelerate movement, to bend the city toward the rhythm of machines.

The North–South connection (French: Jonction Nord-Midi; Dutch: Noord-Zuidverbinding) is a railway link of national and international importance through central Brussels, Belgium, that connects the major railway stations in the city. It is line 0 (zero) of the Belgian rail network. With 1200 trains a day, it is the busiest railway line in Belgium and the busiest railway tunnel in the world. It has six tracks and is used for passenger trains, or rarely for a maintenance train when work is to be done on the railway infrastructure inside the North–South connection itself, but not for freight trains. It is partially underground (around Brussels-Central railway station) and partially raised above street level.

The North–South connection (French: Jonction Nord-Midi; Dutch: Noord-Zuidverbinding) is a railway link of national and international importance through central Brussels, Belgium, that connects the major railway stations in the city. It is line 0 (zero) of the Belgian rail network. With 1200 trains a day, it is the busiest railway line in Belgium and the busiest railway tunnel in the world. It has six tracks and is used for passenger trains, or rarely for a maintenance train when work is to be done on the railway infrastructure inside the North–South connection itself, but not for freight trains. It is partially underground (around Brussels-Central railway station) and partially raised above street level.

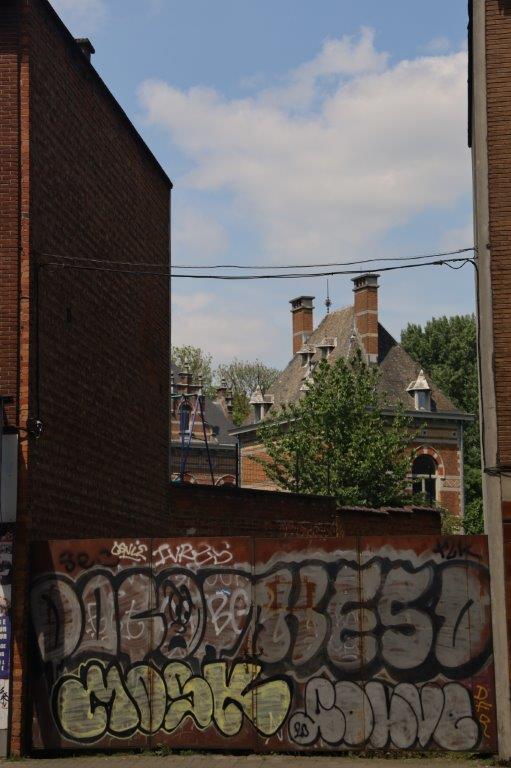

There was no trace of the old Brussels left in this area. The Tour du Midi or Zuidertoren reflects the sky and is an overwhelming presence …

When you stand with your back to the entrance of the Bruxelles-Midi railway Station, go left and follow the Frankrijkstraat.

When you stand with your back to the entrance of the Bruxelles-Midi railway Station, go left and follow the Frankrijkstraat.

The Frankrijkstraat changes into the N266 or Tweestationstraat. Follow this until you reach an old railroad viaduct and keep following it.

The Frankrijkstraat changes into the N266 or Tweestationstraat. Follow this until you reach an old railroad viaduct and keep following it.

Keep following the Tweestationstraat for a long time and cross a roundabout, keep going straight forward.

In French it was called: Deux Gares.

In French it was called: Deux Gares.

As its name suggests, it connects two stations: the South Station, via Frankrijkstraat, and the freight station of Brussels-Klein-Eiland, which was built around 1910 just west of the ring railway. Klein-Eiland, in its extension, was only built in the 1930s. At that time, the railway bridge (see note) spanned the public road with its two northern arches and the station entrances with its two southern arches. Around 2000, the northern road was converted into a cycle path; the central roads became (or remained) public roads, while the southern arch still provides access to the site of the old station.

The even-sided side of the street is formed by a vast block of houses between the railway lines and is bordered by the Zenne, which overhere still flows in the open air.

The even-sided side of the street is formed by a vast block of houses between the railway lines and is bordered by the Zenne, which overhere still flows in the open air.

Watch for a round glass building at the right side of the road, ar a crossing with the Paasemlaan and turn left.

Stay at the left side of this road. Look for a small bridge on your left going to the Paepsem Business Park.

Stay at the left side of this road. Look for a small bridge on your left going to the Paepsem Business Park.

Turn left and walk onto the bridge.

Turn left and walk onto the bridge.

To the left and right you’ll now see the Zenne River.

At the same time as the building of the North South railway line, another disappearance unfolded below: the Zenne itself, the river that once shaped and animated Brussels, muffled and buried under layers of stone and urban planning. The covering of the Zenne was presented as a triumph of hygiene, the end of pestilence, but it was also the silencing of an unruly presence.

The city exchanged a living flow for an invisible conduit; water was denied its song, domesticated until forgotten.

The city exchanged a living flow for an invisible conduit; water was denied its song, domesticated until forgotten.

Together, these two acts — the cutting of the city for the trains, and the burial of its river — mark an epoch when Brussels sought to forget its own chaos, its spontaneous and imperfect life, in favor of order, progress, and control. Yet the absence speaks loudly. In certain places, you still sense the pressure of the hidden river, the disjointed geometry of streets left behind by vanished districts, like phantom limbs of an amputated body.

Together, these two acts — the cutting of the city for the trains, and the burial of its river — mark an epoch when Brussels sought to forget its own chaos, its spontaneous and imperfect life, in favor of order, progress, and control. Yet the absence speaks loudly. In certain places, you still sense the pressure of the hidden river, the disjointed geometry of streets left behind by vanished districts, like phantom limbs of an amputated body.

For me these ruptures do not simply represent destruction. They are also a strange, involuntary architecture of memory. They reveal how a city is never purely what it wishes to be, but what it has tried to erase, what it carries in its depths. To walk along these scarred neighborhoods is to commune with both the dream of progress and the ghosts it concealed.

It was a great feeling of emotional satisfaction to see the Zenne within Brussels, somewhere pop up. It felt like it still defeated all those project designers and the municipal government who had been meticulously planning the total covering of the Zenne river, which was reminding me of the filling of the inner moat in my home town of Deventer in the Netherlands. Filling a moat is even more intrusive then covering a river (well you can’t fill a river because the water needs to go somewhere, hence the covering), but the reasons were similar. The penetrating stench coming from its filthy water and the spread of diseases and plagues of mice and rats. Nowadays the Zenne can’t be seen in most parts of Brussels, but there are projects started to make it visible again in some parts of the city center.

This is the end of the walk. Return using the same route toward the Bruxelles-Midi Railway station, or be brave and use a different route. The Wandelgek took the same route and tried to get to know more about the area.

After having crossed underneath the old railway viaduct, he could see the Palace of Justice from far away. Still an impressive building to watch…

One must learn to read these lines — the buried course of the Zenne, the monumental cut of the railway — like the strokes of an immense drawing whose author is not a single architect but History itself. And perhaps it is in these fissures, where grief and ambition meet, that the true face of Brussels is revealed.

Where the Tweestationsstraat changes back into the Frankrijkkstraat, at the corner of the Frankrijkstraat and the Barasstraat is a Brazilian owned restaurant, named Luciana Xavier, which serves Brazilian cuisine…

The Wandelgek had been walking quite a few kilometers in the heat of the burning sun and was gagging for a nice cold Duvel and some good food, so he entered and immediately fell in love with the place.

The Wandelgek had been walking quite a few kilometers in the heat of the burning sun and was gagging for a nice cold Duvel and some good food, so he entered and immediately fell in love with the place.

First that cold Duvel beer, which was the very first specialty beer The Wandelgek remembered drinking, ever …

First that cold Duvel beer, which was the very first specialty beer The Wandelgek remembered drinking, ever …

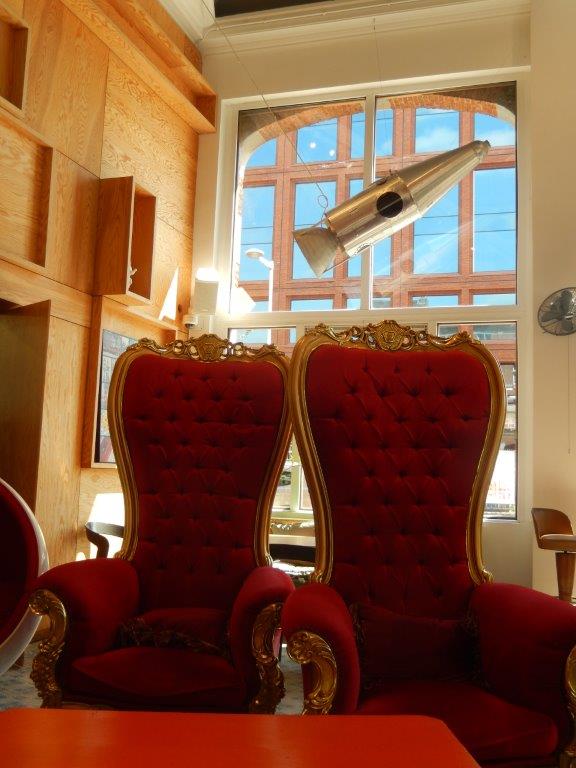

It still is one of his favorite three beers in the world! The bar/restaurant was decorated quite quirky, with bicycles hanging from the ceiling, metal frames, big red chairs and even a rocket

It still is one of his favorite three beers in the world! The bar/restaurant was decorated quite quirky, with bicycles hanging from the ceiling, metal frames, big red chairs and even a rocket

There was a large Brazilian flag hanging at the counter …

There was a large Brazilian flag hanging at the counter …

This really looked like a cozy, friendly place to be in the evening too, but it was a bit too far from the hotel, so The Wandelgek decided not to stay, but to remember this place for future visits to Brussels …

This really looked like a cozy, friendly place to be in the evening too, but it was a bit too far from the hotel, so The Wandelgek decided not to stay, but to remember this place for future visits to Brussels …

The large red chairs and the silver rocket …

The large red chairs and the silver rocket …

The drinks and food were quite good, although it did take a while for them to process the order, but The Wandelgek had all the time in the world and didn’t mind …

The drinks and food were quite good, although it did take a while for them to process the order, but The Wandelgek had all the time in the world and didn’t mind …

He had a mozzarella, tomato, lettuce baguette with the beer …

He had a mozzarella, tomato, lettuce baguette with the beer …

Loved this place with large windows and a lot of sunlight …

Loved this place with large windows and a lot of sunlight …

The toilets were accessed via a corridor decorated with famous Belgian comic book covers …

The toilets were accessed via a corridor decorated with famous Belgian comic book covers …

After a long break…

The Wandelgek left to return to his hotel and seek for a nice beercafé, to spend the evening and the night. He first walked back in the direction of the Brussel-Zuid (Brussels South) Railway Station (and tube station). He bumped onto this strange advertising post, which looked like a smashed glass window with a red white crime scene bar over it. Was this art, or was it really just what it is? A bullet hole at the bottom finished the art work.

The Wandelgek left to return to his hotel and seek for a nice beercafé, to spend the evening and the night. He first walked back in the direction of the Brussel-Zuid (Brussels South) Railway Station (and tube station). He bumped onto this strange advertising post, which looked like a smashed glass window with a red white crime scene bar over it. Was this art, or was it really just what it is? A bullet hole at the bottom finished the art work.

Next The Wandelgek entered the tube station …

Next The Wandelgek entered the tube station …

and returned to Madoux tube station, …

and returned to Madoux tube station, …

… from where he went to his hotel to take a shower and than he left for nearby Liberty Square.

… from where he went to his hotel to take a shower and than he left for nearby Liberty Square.

After an evening and night of drinks and snacks and some interesting conversations , The Wandelgek returned to his hotel. He had planned a new walk for the next day and wanted to start early. 2 days left to enjoy more of Brussels and learn more of François Schuiten’s view of Brussels as well. Until now it had been a really rewarding visit.